Immunize Against Inflation Risk? Protecting an Insurance Portfolio Against Persistent Inflation

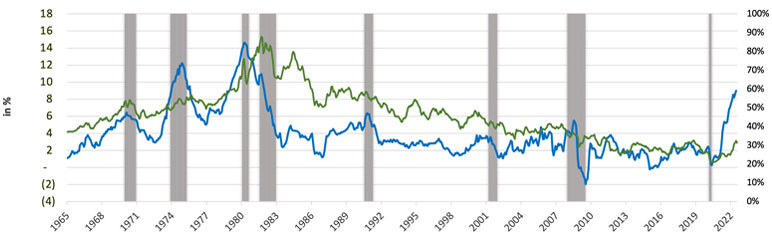

Decades of falling inflation can easily be seen through lower bond yields if one were to use them as a proxy—both the 10-year note and the 30-year bond hit all-time lows during the last decade. Developed markets yields in Europe went further into the negative territory. For consumers, the record lows on 30-year fixed mortgage rate in 2020 can highlight the falling costs of borrowing on their home loans. Year-over-Year Core CPI (Chart 1) and inflation expectations hit all-time lows during the last decade. So did the fed funds rate.

Chart 1

Core CPI YoY Change and 10-year Treasury Rate

The consumer price index (CPI) from the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the personal consumption expenditures price index (PCE) from the Bureau of Economic Analysis are common measures of inflation that are monitored by analysts. The CPI tends to show more inflation than the PCE. The federal government uses the CPI to make inflation adjustments to some of the of benefits disbursed, such as Social Security—interpreted as the pricing of liabilities due in the future being adjusted for by CPI inflation. The Federal Open Markets Committee on the other hand highlights PCE inflation in its quarterly economic projections and discusses its longer-run inflation goal in terms of headline PCE.

Conventional models of inflation state that considerable increases in government spending depress the purchasing power of currency and thus drive inflation higher. The monetarists propose that the excess increases in the quantity of money is responsible for subsequent increases in the price levels, whereas the Keynesians theorize that the excess increases in the total expenditure (e.g., investment expenditure and government expenditure) are the sources of excess demand and hence inflation. Without accepting any of the theories behind inflation risk, we can agree that the Covid-19 pandemic is forcing a rethink in macroeconomics. After the passage of the $3 trillion CARES Act and the Fed's unconventional intervention in markets, including the corporate bond markets through purchases of Corporate ETFs, inflation initially has risen only somewhat.

But something did change in the last few quarters, and we must be prepared for a change in inflation going forward. The Congressional Budget Office estimated in 2020 that even without the new stimulus acted, the gap between actual and potential output would shrink dramatically by the end of 2021. The current stimulus is projected to be at least three times the size of output shortfall, about 13 percent of total GDP, specially amid loose financial conditions, stoking fears of inflation risk among some economists and policy makers. Unemployment too is falling fast, and employment has regained the levels before the pandemic. In particular, the indicators in the housing market, sales of existing homes, new home sales and median prices are all suggestive of a persistent surge in inflation.[1] What's more, retail spending and increasing consumer demand may surprise to the upside as consumers spend around $1.5 Trillion in savings that were accumulated last year affected by pandemic related closures. The last time core-goods inflation exceeded core-services inflation was in 2011. Both high headline and core inflation has stoked fears that inflation may not be transitory and is rather persistent.

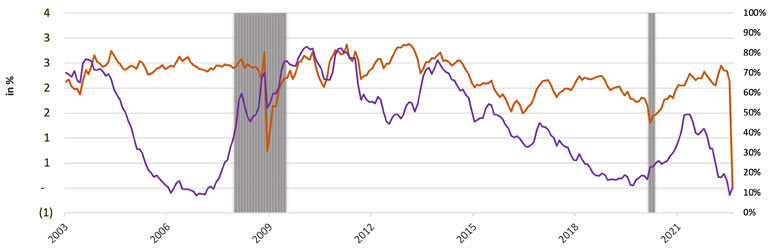

Larry Summers, the senior U.S. Treasury Department official throughout President Clinton's administration, has urged caution[2] and has pointed out that market inflation expectation measures have increased more than during any comparable period in this century, except for moments when inflation expectations were in the basement, as in 2008 or the early days of this pandemic. However, the treasury curve as measured by the difference between the 10-year yields and the 2-year yields has steepened starting late 2020, only to flatten further by mid-2022 (Chart 2). The five year and five year forward inflation expectations have similarly steepened in 2021 only to flatten thereafter. In current months, such fast moving indicators have steered the debate into the nature of inflation being transitory or persistent[3].

Chart 2

Five Year, Five Year Forward Inflation Expectation and 10-year Minus 2-year Treasury Rate

Date source: fred.stlouisfed.org

U.S Recessions are shaded

Insurers are affected by specific components of CPI and inflation in general, and both by rapidly falling and rising inflation. Increasing costs of medical care increase reimbursements by health insurers. Long-term care products needed repricing in the aftermath of lower interest rate regimes as well as increasing cost of care. Auto insurers are affected by increasing or falling cost of automobiles and parts. Home insurers are impacted by Home Price Inflation and climate costs. Higher inflation can also erode the value of bond investments that insurers currently hold. Persistent lower inflation lowers future expected return on investments and increases the value of liabilities compared to assets. Life insurers, property-casualty insurers and health insurers are all impacted by inflation to various degrees.

I think it is prudent to raise an alarm over the persistency of current inflation risk as part of a proactive risk management strategy. There is a chance that the current rise in inflation may subside as has happened numerous times during the past decades, but that does not preclude the need to build a robust portfolio that can withstand a more sustained and persistent inflation shock. I hereby present a framework to construct an optimal portfolio that protects investors against persistently higher inflation.

The Three Musketeers Driving Inflation

There are three dynamic factors that play a considerable role in driving inflation. One can study inflation by understanding the interplay of the following three players:

- Consumers—Consumer spending and available goods inventory dictates prices. If consumer confidence is high, and spending is robust, prices can rise. Early during the Covid pandemic, production stagnated while spending continued depleting inventories causing prices to rise. As production stabilized, the rise in prices became moderate.

- Lenders and investors—During periods of innovation, creativity or during periods of loose monetary policy, lenders may invest in projects that are unsustainable in the long run. But during the initial period of investment frenzy, more money chases few projects creating an imbalance and leading to inflation in the short term.

- The Federal Reserve—The Fed has a slew of tools to keep inflation under control. The Fed pays interest on reserves to banks, which discourages them from loaning money to the private sector. The Fed’s term deposit facility acts similar to a checking account that converts deposits into fixed maturity at higher interest, which keeps monies out of the monetary base. Borrowing through reverse repos on the other hand enables the Fed to reduce the monetary base without selling assets. During the financial crisis of 2008, treasury loans were also made available to foreign central banks through the Department of Treasury using liquidity swaps.

The Basics of the TIPS Market

Treasury inflation-protected securities (TIPS) were issued for the first time in the United States in 1997. It would offer the buyers of the securities a means to hedge inflation risk. The US treasury department on the other hand would take on inflation risk and benefit by not having to pay an inflation risk premium on its securities, thus lowering the expected borrowing costs. The securities would also provide a market-based measure of inflation expectation by comparing against similar maturity nominal securities.

TIPS are conceptualized to offer a real rate of return, and thus, help investors earn a somewhat assured amount of protection against inflation. When investing in TIPS, investors give up the certainty of a predictable income stream in exchange of the certitude that their investment will preserve its purchasing power in case of rising inflation. One can thus infer that for that assurance, TIPS pay a slightly lower interest rate than comparable maturity nominal treasury securities. The principal amount is adjusted daily based on the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U). An increase in consumer prices is reflected in higher principal and interest payments to the TIPS holders, and vice versa.[4] The change in CPI-U is represented by a factor that is reflected in the adjusted principal value. Newly issued TIPS have a factor of 1.0. In an inflationary period, the factor will go up; in a deflationary period, it will go down. Since the coupon is paid on the outstanding principal value, the semi-annual payments fluctuate with time. At maturity, a TIPS investor is paid the greater of the adjusted or the original issued principal.

When comparing bonds, investors typically assess the difference in yields between TIPS and comparable nominal Treasury bonds. The difference in yield is known as the breakeven inflation rate. For example, if a 10-year TIPS yields 0.50 percent and a 10-year nominal Treasury note yields 1.75 percent, then the breakeven inflation rate is 1.25 percent. If inflation ends up being higher than 1.25 percent over the life of the bond, then TIPS should provide a higher total return than comparable nominal Treasuries.

In general, when inflation heats up, both interest payments and the expected principal payback for TIPS go up, hence the "inflation protection" that makes it better than nominals.[5] However, the "real interest rate" usually goes up as well when inflation heats up, since the demand for capital usually increases. TIPS protect us against the CPI part, but not the "real interest rate" part. There is thus a favorable range for TIPS to perform relatively well versus nominal treasuries, when CPI is between 1 and 1.5. If CPI is lower than this range, the market typically is in a stressed mode, perhaps due to falling equities, or increased credit risk or any sectoral stress in commodities, banking, or technology crisis. In such a scenario real yield itself falls and TIPS may do well or act as a hedge. However, even in this case, nominals treasuries will outperform TIPs due to both falling inflation and real yields. Both TIPS and nominals have negative convexity, in terms of price, with respect to CPI. TIPS outperform nominals in the more normal environment, or when we are in or above the convenient range of 1 to 1.5 percent CPI Inflation.

Using Inflation Derivatives for Hedging Inflation Risk

A well-developed and functioning derivatives market on an underlying security indicates usability and reliability of the security and market implied measure derives from it. The inflation derivatives market has flourished over time. Inflation derivatives are designed to transfer the inflation risk between two parties. Inflation swaps are the preferred way to express views by issuers, hedgers, and speculators alike.

Consider a real estate company that may want to reduce their natural exposure to inflation risk, while a pension fund may want to cover their natural liabilities to this risk. Inflation derivatives provide an efficient way to transfer this inflation risk.

The many participants in the inflation derivatives market are utilities, project finance, banks, pension funds, corporates managing ALM, mutual funds, insurance companies, and hedge funds. Banks want to receive inflation on swaps to hedge inflation-linked retail products. Insurance companies and pension funds want to receive inflation to match their long-term inflation-linked liabilities. The market makers and investment banks can thus facilitate matching the receivers and payers of inflation. Furthermore, a derivative based inflation swap can be replicated using a portfolio of a zero-coupon inflation-linked bond and a zero-coupon nominal bond, bringing relative value players and hedge funds into the market. So, in the absence of natural payer or receiver, the banks can hedge using cash inflation bonds, giving a boost to overall market size. The natural receivers and payers of inflation help create a synthetic market and popularize the use of derivatives. In some cases, to juice up yields, a conventional receiver may end up paying inflation through a derivative to convert to a higher fixed yielding investment.

Mortgage-backed Securities and Derivatives as Inflation Hedge

Mortgage-backed Securities (MBS) are bonds that represent an ownership interest in a pool of residential mortgage loans. Homeowners make mortgage payments that are pooled each month and then “passed through” to MBS holders in the form of principal and interest cash flows. Agency MBS are created by one of three government-sponsored agencies: Ginnie Mae, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac bonds aren’t US government guaranteed, but they are under conservatorship of the US government and regulated by the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA). Ginnie Mae bonds are backed by the full faith and credit of the US government and their credit is comparable to US Treasury securities. Both Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac MBS generally offer higher current yields than Ginnie Mae MBS in order to compensate for their slightly lower perceived credit quality. The primary risk to investors is the prepayment risk. Typically, when interest rates fall, homeowners refinance their mortgages to secure a lower rate in order to achieve lower monthly payments. As a result of such refinancing events, mortgages are paid off prior to maturity and the MBS investors are confronted with reinvesting that money at a lower prevailing interest rate.[6]

It is this prepayment risk that can be attractive to investors when interest rates are slowly rising. In case of an inflationary bout that afflicts the interest rates market, the prepayment risk will remain diminished, due to lack of refinancing, causing the values of MBS to outperform, thus making them a suitable investment or a hedge. Mortgage derivatives like Inverse IOs act similar to curve steepeners that may benefit during rising inflation.

Portfolio Construction Using the Black-Litterman Model

The Black-Litterman (BL) optimization model is a combination of the capital asset pricing model (CAPM) and the modern portfolio theory. It allows for a subjective view parameter in a quantitative model where in the absence of such views, the investor will own a passively managed market equilibrium portfolio. The model imposes active viewpoints on a passively managed market cap weighted portfolio.[7] Mathematically, the model uses a Bayesian approach to combine the subjective views of an investor regarding the expected returns of assets with the market equilibrium vector of expected returns—the prior distribution, to form a new, integrated estimate of expected returns. The resulting new vector of returns, the posterior distribution, leads to intuitive portfolios with discernable portfolio weights.

We chose the BL model to avoid the usual pitfalls of the classic Mean-Variance (MV) optimizer—to avoid concentrated portfolios, input sensitivities of predicted and expected returns and volatilities, as well as the naïve assumption that the returns are normally distributed. We also wanted to accommodate shorting (using negative weights) to maintain a curve steepener, should the model indicate so.

In the following hypothetical example of an insurance bond portfolio, although diversified across investment grade, high yield, emerging markets, TIPS, MBS, municipals and U.S. and global bonds, we have not used exposure to equities or commodities to hedge against inflation. This is because insurance companies, primarily life insurance, may be either reluctant to invest in them or may have rules barring investing in them. All bond prices, be it corporates or sovereign EM respond to changes in real and inflation rates and may have correlations that limit diversification. We think that the BL model overcomes this correlation problem otherwise seen in classical a MV optimized portfolio.

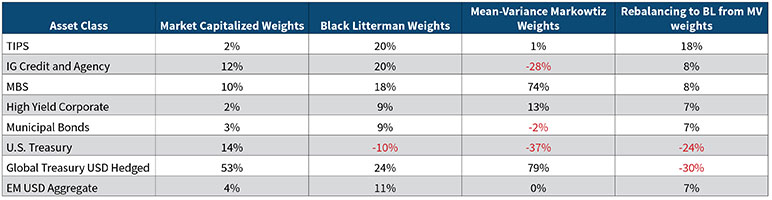

Hypothetical TIPS and MBS Allocation in an Optimal Portfolio

Table 1 below shows a hypothetical portfolio using monthly historical prices starting in 1997 from the Bloomberg Barclays Indices, representing the eight sectors ranging from TIPS to EM USD Aggregate. The market weight, index composition, price history for these indices are widely used in the industry. We impose four constraints on the optimization routine; a) returns from TIPS to be equal to or more than the past average long run returns, b) returns from MBS to be equal to or greater than the lowest second quartile of returns in the past, c) an equally weighted TIPS and MBS portfolio that outperforms a combined US and Global Treasury portfolio, and d) TIPS slightly outperform the MBS index, given that in an inflationary regime, the Fed may taper their MBS holdings in near future.[8]

One can see that the BL optimized weights allocate a higher percentage to TIPS and MBS indices (Table 1). Additionally, the short on the US Treasuries (the index components are weighed heavily toward the long end) implied from the Black-Litterman weights conveys positioning for a “curve steepener.”

Table 1

The Black-Litterman Portfolio Allocation Weights

When investors expect stronger economic growth and higher inflation leading to higher interest rates, they can hedge their inflation risk through a curve steepener—by buying short-dated treasuries and shorting longer-term Treasuries through futures, swaps, payer swaptions or other derivatives. It is noteworthy that Global Treasuries maintain a sizable weight as well, implying that the rise in inflation and curve steepness may be limited to US in near future, given the large stimulus spending.

Underwriting Liabilities Priced to Inflation

Finally, one of the best ways to hedge against inflation is to correctly bake it into pricing models used to underwrite liabilities, be it P&C, Health or Life contracts. Insurers also provide consumers with inflation protection schemes under various contracts, e.g., inflation riders may be available for long-term care policies. Pricing such riders embedded in the policies is extremely crucial both for the profitability and sustainability of the insurer as well as the protection availed to the policyholder. Modern portfolio theory highlights the distinction between risks that are systematic—risks that are related to economy wide factors and others that are random in nature or unsystematic risks. Systematic risks like inflation are of major concern to both investors and consumers. A substantial charge may be required to bear such systematic risks, and thus optimal pricing and hedging strategies must be studied and implemented. Inflation may be the biggest risk facing the industry in half a century. Pricing insurance products to capture the forthcoming inflation risk is the most economically judicious step to take for all insurance professionals.