An Interview with Ruodu Wang

Expanding Horizons, November 2021

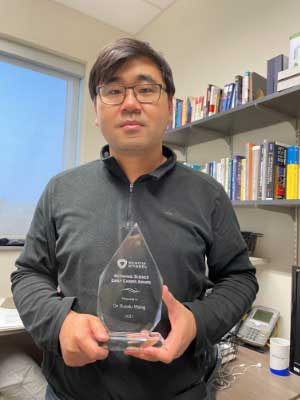

This month, Expanding Horizons had the opportunity to interview Ruodu Wang, the winner of the Society of Actuaries’ (SOA’s) first Actuarial Science Early Career Award.

Expanding Horizons (EH): Congratulations on winning the inaugural SOA Actuarial Science Early Career Award. Can you tell us about your background?

Ruodu Wang (RW): I was born in Beijing, China, in 1984. I grew up and got most of my education in the same city including a BS in mathematics and an MS in financial mathematics, both from Peking University. I studied with Jingping Yang, a leading researcher of actuarial science in China. In 2009, I went to the United States to study for a PhD in mathematics at Georgia Tech. My thesis advisor was Liang Peng, an established statistician with a strong interest in actuarial science. I got my PhD in 2012, and since then I have been working at the Department of Statistics and Actuarial Science at the University of Waterloo in Canada, as an assistant professor (2012–2017), an associate professor (2017–present), University Research Chair (2018–present), and Sun Life Fellow (2021–present).

EH: How did you get into the profession?

RW: I assume by “the profession” you mean being an academic. I think it was rather random. During my time at college, I thought my career would be in the gaming industry. When I was finishing my PhD, I was not sure what I was going to do. My PhD advisor suggested that I could try academic positions. I got an assistant professorship offer from the University of Waterloo, which I believe has the best research unit in actuarial science. I thought I would try it to see whether I’d like it, and now I’m here.

I would like to share two small incidents that made this possible. During my first term at Georgia Tech, I spontaneously attended a seminar (hosted in a different department) by Roger Nelsen, the author of a famous book on copulas. During his talk, he mentioned an open question, motivated by multivariate Spearman’s rho:

What is the minimum of the expected product of three standard uniform random variables?

The question looked so innocent that I immediately started working on it after Nelsen’s talk. It turned out that this question and its variants had a long history of failed attempts (from famous researchers), which I did not know. I visited China for Christmas that year, and again spontaneously, I discussed this question with Bin Wang, then a PhD student at Peking University. Together we invented the theory of mixability, a new concept in the field of dependence modeling, in our 2011 paper,[1] which answered Nelsen’s question with much more generality. In this and follow-up papers, it was Bin who came up with the sophisticated proofs of the central results in this area; without him, I would not have been able to do anything. This stream of work was developed during my PhD study but independent of my thesis on high-dimensional statistics, and it led me to long-term collaborators and friends, in particular Giovanni Puccetti and Paul Embrechts. This pleasant and rewarding research experience pushed me in the direction of becoming an academic.

EH: Did you receive any support that has substantially helped you in your early career?

RW: First of all, my MS advisor, Jingping Yang, and PhD advisor, Liang Peng, have always been inspirational. I was very lucky to have their support ever since I was a graduate student. The University of Waterloo is exceptional in helping young scholars to establish their careers. In addition to many brilliant colleagues who are top actuarial researchers, my department allowed (indeed, encouraged) me to spend a few months at ETH Zurich (to which I was invited by Paul Embrechts) every year since the beginning of my tenure-track position. This valuable opportunity helped me to establish numerous academic connections that eventually led to many joint publications and friendships. Paul has helped and supported me tremendously throughout my academic career, with pleasant and fruitful collaborations and, more importantly, personal guidance. Many senior and established actuarial scholars have been extremely kind, supportive and helpful to me since I started my career; everybody in the community is really nice. I was also very fortunate to meet so many brilliant collaborators and students. Generous financial support from the SOA and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) is, of course, crucial to the success of any scholar.

EH: What challenge did you encounter as an actuarial researcher?

RW: I think there is a unique challenge for most actuarial researchers, which is the need to master knowledge and techniques from multiple scientific disciplines, including mathematics, data science, economics, finance, insurance and operations research. A good actuarial scientist needs to be knowledgeable about, and communicate with, researchers in almost all these disciplines, and some of these fields are growing very fast. Typically, a researcher’s educational background may be excellent in one or two of these disciplines, but it is rare or even impossible to have a strong background in all disciplines. Therefore, there are always a lot of new things for an actuarial scientist to learn, and one constantly faces competition from researchers in other fields, such as data scientists or financial engineers. On the other hand, communicating with practicing actuaries and making research outputs practically relevant are important but not easy tasks for a junior professor who is fighting his or her way into tenure.

EH: You have a lot of academic achievements. What are the most important ones?

EH: You have a lot of academic achievements. What are the most important ones?

RW: Perhaps one of my main academic achievements has been to establish strong links among several scientific fields. As I mentioned before, dependence modeling has been a central part of my research since my PhD. This has led to a stream of work on robust risk aggregation,[2] where the main aim is to determine values of various risk measures under uncertainty in modeling dependence.

The concept of mixability plays an important role in multimarginal mass transportation theory, and it has recently been applied in many other major scientific fields, including statistics,[3] operations research,[4] and economic theory.[5] I am very excited to see its current development.

The theory of risk measures has become the largest percentage of my current work. A contribution that I am particularly proud of is an axiomatic characterization of TVaR/ES with Ricardas Zitikis.[6] Risk sharing is intimately linked to insurance and economics, and it has also become one of my core research streams since 2018.[7]

In the past few years, part of my research has been directed into multiple hypothesis testing and selective inference. Vladimir Vovk and I introduced the concept of expectation-values (e-values),[8] which I believe is receiving increasing attention from the statistics community.

EH: Any personal philosophy with regard to actuarial research and teaching?

RW: I always felt that actuarial researchers and teachers should not confine themselves to the traditional territory of actuarial science. They should always learn and borrow from other fields and make them specialized for actuaries, and conversely, they should export and communicate findings in actuarial science to other fields. I’ve benefited tremendously from interacting and collaborating with brilliant researchers outside actuarial science. As for education, the professional exams are important, but they should not be everything for actuarial students. At Waterloo, teaching and research in actuarial science are way beyond what is traditional for actuaries. For instance, we are fortunate to have the resources to currently offer 44 different undergraduate and graduate actuarial courses (different PhD topic courses are counted together as one course).

EH: What would you suggest or advise someone who is just entering the actuarial profession in either the industry or academia to do?

RW: I do not think I am in a good position to give advice for people who enter the industry. For academic actuaries, from my own experience, attending seminars and discussing questions with peers, even randomly, can be extremely helpful. I would suggest young people try to find and carry out research projects on their own as early as possible, because by desperately searching and thinking, one learns a lot. I also completely agree with the words of Paul Embrechs:

. . . surely the family situation has to fit in with a developing academic career, especially as longer stays abroad coupled with not particularly high beginning salaries are the norm. Further, it is important to get acquainted early on with all major aspects of academic life, these include, besides the obvious teaching and research, other duties on the (inter)national academic scene which constitute good academic citizenship. Finally, being an academic in whatever university environment (and I was both at very small institutions as well as at world class ones) you must realise that it is your personal involvement that will finally contribute to your institutions’ success.[9]

EH: What is your vision about the future of actuarial research?

RW: It is not surprising that I would say the future of actuarial research will be more intimately linked to data science, operations research, finance and innovative (financial and insurance) technologies. Nevertheless, I would like to emphasize that there should be a clear boundary between actuarial research and research in these fields. If the boundary is blurred, then the other fields will gradually take our ground, as they often have more monetary resources and bigger research communities. There will be new active and practically relevant future research areas that are specific to actuarial science, possibly established and developed by younger researchers. I guess this is more a hope than a vision.

EH: What do you see as the biggest challenge of the actuarial profession?

RW: Related to an earlier point, I believe the greatest challenges come from the competing disciplines, especially from data science, which has been attracting many talented students. It is crucially important for us to emphasize and enhance the advantages of an actuarial education compared to an education in data science, as well as the advantages of an actuarial career. As I mentioned before, a concrete boundary between actuarial science and related fields is essential in both research and practice. The SOA has been tremendously important in this regard. Similar to other STEM disciplines, equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI) needs to be improved further in the actuarial profession, and this leads to many challenges.

EH: Why and how do you think the insurance industry should support academic actuarial research?

RW: I could see three main reasons for industry support and collaboration, each of equal importance. The first reason is that academic research helps practicing actuaries (and insurance companies in general) to better manage risks and to better understand the world quantitatively. Many now-standard statistical and computational methods in insurance originally stemmed from academic research, and the ML/AI era has brought so many new questions to explore. In Europe, insurance companies and academics collaborate intimately; for instance, I have interacted with several industry-sponsored PhD students from ETH Zurich, who made excellent contributions to both academic research and industry practice. In North America, this kind of collaboration is unfortunately still a bit underdeveloped, but a good trend has been observed in the past few years, thanks to the efforts of many colleagues in our profession.

The second reason is that we train next-generation actuaries. If our research is innovative and cool, then we attract more talented young students. This requires support and appreciation from the industry. Eventually, it is the next generation that matters, and both the industry and academia benefit from having the best students.

The third is about the reputation of the scientific discipline. Actuaries are known to work for a better world by keeping people’s lives financially safe and stable. The high regard for a scientific discipline cannot be maintained if scholars and research outputs in the field are not considered the best in the world. Actuarial science needs to stay strong as an active and reputable scientific discipline for a better and safer world.

As for the question of how, I think we should really learn from the Europeans. Insurance companies fund many research projects through grants, collaborations and, most importantly, graduate students and postdocs. Having an open mind is also important, and this means supplying and discussing practical challenges, questions and relevant data with researchers.

EH: What might someone be surprised to know about you?

RW: As you probably know, I was a competitive Starcraft player, so this is not really surprising. Another small fact may surprise someone: I have visited more than 50 countries (before COVID) and all seven continents.

Statements of fact and opinions expressed herein are those of the individual authors and are not necessarily those of the Society of Actuaries, the editors, or the respective authors’ employers.

Ruodu Wang, PhD, is an associate professor and University Research Chair at the University of Waterloo. He can be reached at wang@uwaterloo.ca.