Incorporating Accrual Balances in the LFPB under LDTI

By Kevin Cao and Jack Zheng

The Financial Reporter, September 2024

Accounting Standards Update No. 2018-12, Financial Services – Insurance (Topic 944): Targeted Improvements to the Accounting for Long-Duration Contracts (LDTI) has been effective for most large, public business entities since 2023 and will be effective for other insurers in 2025.

One of the targeted improvement areas under LDTI is the liability for future policy benefits (LFPB). While LDTI does not directly impact the measurement and calculation of claim liabilities, including the liabilities for claims incurred but not reported (IBNR) and in course of settlement (ICOS), with the change to the LFPB measurement model, claim liabilities need to be considered and incorporated when calculating LFPB. Similar considerations also apply to premium accrual balances such as due and advanced premiums.

Appendix A of the AICPA Audit and Accounting Guide – Life and Health Insurance (AAG-LHI), paragraph A.17 notes that the future benefits in LFPB “represent all payments under the contract, including future expected claims and claims for which the disability, morbidity, or other insurance event has occurred but for which claims have not yet been paid.” Question 4.13 from the American Academy of Actuaries’ LDTI Practice Note states that “under AICPA guidance, the correct way to incorporate changes in a claim liability into the net premium ratio is by including all cash flows, historic and projected, directly into the net premium ratio calculation without an interim step of calculating a separate claim liability,” and that “when the correct way is impractical, various techniques have been proposed to include changes in the claim liability in the net premium ratio.” Though the guidance clarifies the need for incorporating claim liabilities and premium accrual balances in the LFPB under LDTI, companies may still have questions on how to incorporate these accrual balances, given there are limited details available around the techniques used in practice.

In this article, we explore this topic further by first demonstrating the need for incorporating claim liabilities and premium accrual balances in the LFPB under LDTI. We then look at two potential approaches of incorporating these accrual balances.

Potential Approaches

Prior to LDTI, the LFPB was usually calculated at a policy level with a locked-in net premium ratio (NPR) calculated at policy issue date. IBNR/ICOS and premium accruals were typically estimated and accounted for separately from the policy LFPB. Under LDTI, LFPB is now calculated at a cohort level with one NPR for a cohort, and the NPR is recalculated at each measurement date to reflect actual experience and changes in projected cash flows. To ensure consistency between actual historical cash flows and projected future cash flows, care must be taken to develop an internally consistent set of cash flow definitions to be applied in the NPR and LFPB calculation. As a result, companies must define both the basis and corresponding cash flows to be included in the model. Two potential approaches for incorporating claim liabilities and premium accrual balances into LFPB under LDTI are (a) a cash basis approach and (b) an accrual basis approach.

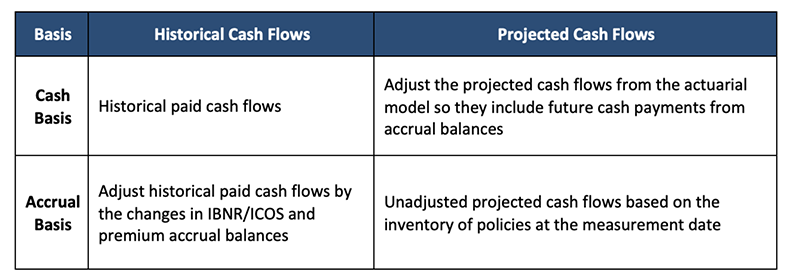

Under the cash basis approach, actual historical cash flows for the NPR calculation include only premiums received and benefits paid in cash. Projected cash flows for the LFPB and NPR calculation would similarly include cash items, such as future expected cash items from accrual balances. Under the accrual basis approach, actual historical premiums and benefits represent the earned premiums and the total benefits recognized in the income statement, whether or not such amounts were settled in cash. Table 1 summarizes how the historical and projected cash flows for LFPB and NPR would be impacted when using cash basis versus accrual basis to incorporate IBNR/ICOS and premium accruals.

Table 1

Summary of Potential Approaches

Illustrative Examples

To help demonstrate the points above, we illustrate the concepts through three examples by looking at the LFPB calculation for a sample 10-year level term product:

- Incorrect approach: accrual balances not reflected

- Potential approach 1: cash basis

- Potential approach 2: accrual basis

For simplicity purposes to illustrate the key concepts, only IBNR will be included, and we are using a term life insurance product so there are no long-tail claim liabilities. In practice, similar considerations would apply to ICOS and premium accrual balance and to products with long-tail claim liabilities (such as long-term care). The examples assume a 3% discount rate (A-rated bond yield), with premiums paid at the beginning of year and benefits paid at the end of the year. IBNR of $9,709 is established at the end of year 1. It represents the present value of IBNR claims, which are expected to total $10,000 and, on average, occur one year after the valuation date.

Example 1 – Not Reflecting IBNR in the LFPB Calculation

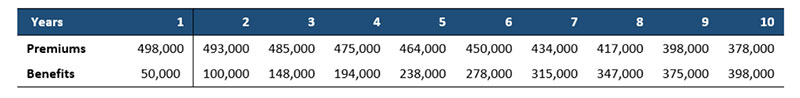

In the first example, we illustrate the case if the company records IBNR but does not consider the IBNR in the LFPB calculation at the end of year 1. The annual cash flows (CFs) and liability balances as of the valuation date (end of year 1) are summarized below, with actual cash flows included in year 1 and estimated cash flows thereafter. (see Table 2 and 3)

Table 2

Actual and Projected CFs

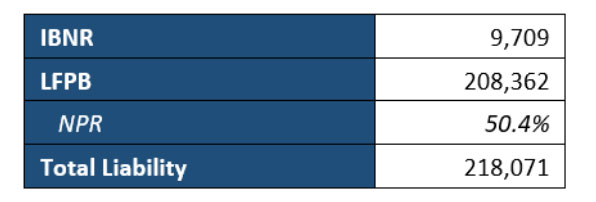

Table 3

Balances as of the Valuation Date

The LFPB as of the valuation date above is calculated as the following:

LFPB = Present value at the end of year 1 (PV1) of [projected benefits from years 2 to 10] – NPR * PV1 [projected premiums from years 2 to 10]

- NPR is recalculated at end of year 1 = PV0 [actual benefits from year 1 and projected benefits from years 2 to 10] / PV0 [actual premiums from year 1 and projected premiums from years 2 to 10]

The issue in this example is that given the incurred-but-not-reported claims, the term cohort is less profitable than the NPR would suggest. When IBNR is not reflected in the LFPB calculation, the NPR is understated, resulting in excess reserves.

In the following examples, we illustrate incorporating IBNR claims into the LFPB calculation following the cash and accrual bases. Notice how the total liability would compare against Example 1.

Example 2 – Incorporating IBNR under Cash Basis

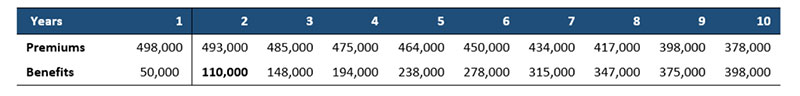

In the second example, we incorporate IBNR in the LFPB calculation on a cash basis. The historical cash flows are the same as the first example, but the projected cash flows are adjusted to reflect the runoff of the IBNR as the estimated claims turn into cash payments. That is, the projected benefit cash flows at the end of year 2 are increased by $10,000 (i.e., from $100,000 to $110,000). Cash flows for other years are unaffected. The formulas for calculating LFPB including NPR are the same as Example 1 above. The updated cash flows and related balances as of the valuation date are summarized below. (see Tables 4 and 5)

Table 4

Actual and Projected CFs

Table 5

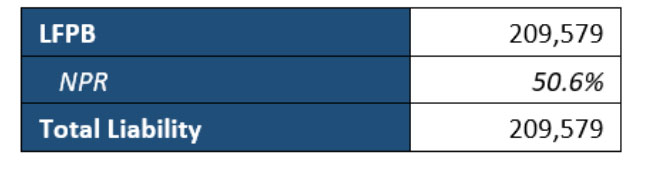

Balances as of the Valuation Date

With the IBNR claim directly incorporated into the LFPB, a separate IBNR liability is no longer required, though it is often removed from the LFPB and reported separately on the balance sheet. The NPR is higher compared to Example 1 due to reflecting the IBNR claim in the projected cash flows for the LFPB calculation. The total liability the company holds in this example is $209,579, which is $8,492 lower than the total liability in Example 1.

Example 3 – Incorporating IBNR under Accrual Basis

Alternatively, the IBNR liability may be incorporated into LFPB calculation using an accrual basis. Under this approach, a separate IBNR liability is calculated, and the change in IBNR each period is included along with the historical paid cash flows in the NPR calculation. In the example, the historical death benefits in year 1 is increased by $9,709, which is the change in the IBNR from beginning to end of year 1. Projected cash flows are unaffected and are the same as in Example 1. The formulas for calculating LFPB including NPR are the same as Example 1 above. The updated cash flows and balances as of the valuation date are summarized below. (see Tables 6 and 7)

Table 6

Actual and Projected CFs

Table 7

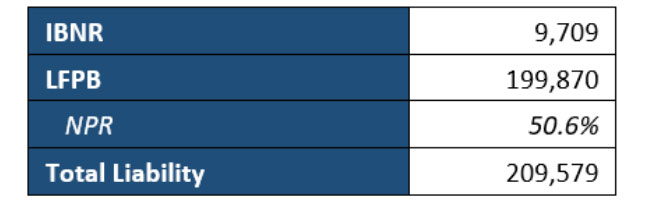

Balances as of the Valuation Date

As shown above, under the accrual basis, the IBNR liability is typically held separately from LFPB. The NPR is also higher compared to Example 1 due to reflecting the change in IBNR as part of actual historical cash flows in the NPR calculation. The total liability the company holds is $209,579, which is the same as the cash basis approach shown in Example 2. This is as expected and is a consequence of the IBNR being estimated using a discount rate and timing of cash flows consistent with those used in the cash-basis calculations.

Additional Considerations

As demonstrated in the examples above, given the change to the LFPB measurement model under LDTI, accrual balances will need to be considered and incorporated in the LFPB, and we have illustrated two potential approaches to do it.

We offer the following additional observations as concluding thoughts:

- In Examples 2 and 3, despite incorporating IBNR in the LFPB calculation, a small inconsistency remains. This is because given the expectation that there is an IBNR claim, the projected future premiums and future benefits for LFPB calculation should now be lower (that is, less in premiums will be collected in the future and less in benefits will be paid out given that an unknown claim has already happened). In practice, the projected cash flows typically are not adjusted, because the impact is small and the policies associated with the IBNR liability are often not practical to identify. The excess reserves that result represent an “in-force lag” issue, an inconsistency between the in-force policies for which cash flows are projected in the actuarial models and the actual in-force at the valuation date. For ICOS, depending on the materiality of the balance, some companies would adjust the valuation in-force file to remove those terminated policies. This would eliminate the excess reserves for policies associated with ICOS.

- The accrual approach appears to be the more popular option elected by companies under LDTI, potentially given that the accrual approach aligns better with how IBNR/ICOS have been treated under pre-LDTI (i.e., calculated and reported separately).

The views reflected in this article are the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Ernst & Young LLP or other members of the global EY organization, the Society of Actuaries, or the editors of The Financial Reporter. The information presented has not been verified for accuracy or completeness by Ernst & Young LLP, the Society of Actuaries, or the editors of The Financial Reporter, and should not be construed as legal, tax, or accounting advice. Readers should seek the advice of their own professional advisors when evaluating the information.

Kevin Cao, FSA, MAAA, is a consulting senior manager at Ernst & Young LLP. He can be reached at kevin.cao@ey.com.

Jack Zheng, FSA, MAAA, is a consulting senior manager at Ernst & Young LLP. He can be reached at jack.zheng@ey.com.