Intimate Partner Violence: The Shadow Pandemic Part 1: Background Briefing

By Jananie William

Health Watch, March 2021

Editor’s note: This paper discusses experiences of violence which some readers may find distressing. Statements of fact and opinions expressed herein are those of the individual authors and are not necessarily those of the Society of Actuaries, the editors, or the respective authors’ employers.

. . . violence against women is not a small problem that only occurs in some pockets of society, but rather is a global public health problem of epidemic proportions, requiring urgent action.

It is time for the world to take action: a life free of violence is a basic human right, one that every woman, man and child deserves.[1]

In this series of papers, we shine a light on the global public health epidemic of intimate partner violence (IPV). This first paper presents background information on the problem. Other papers will explore the nature of IPV in different contexts, including during COVID-19, and how we can work collectively toward a world free of IPV. Our aim is to start much-needed conversations and research projects within the actuarial community on this important topic.

What Is Intimate Partner Violence?

IPV includes physical violence, sexual violence, stalking and psychological aggression (including coercive tactics) by a current or former intimate partner.[2] IPV does not discriminate and exists across race, age, socioeconomic and demographic groups, but it mainly affects women and children.[3] Disturbingly, the most common form of violence that women experience is from an intimate partner.[4] The term “domestic and family violence” includes IPV but also extends to violence against children and elders within the family setting.

A common misconception about IPV is that the violence is limited to physical assault. However, in the context of IPV, the term “violence” encompasses both physical and nonphysical types of abuse, which include but are not limited to homicide; rape; sexual and physical assault; coercive control; threats; intimidation; isolation; stalking; and emotional, psychological, financial and online abuse.[5]

There is growing global recognition that IPV is a serious but preventable public health problem.[6] The expanding evidence on the prevalence and consequences of IPV show that urgent international action is required. Globally, 30 percent of women experience physical and/or sexual forms of IPV in their lifetime.[7] There is considerable variation by region, with estimates ranging from 16 percent to 66 percent across the world.[8]

Figure 1

Prevalence of IPV in the United States

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/fastfact.html.

The most recent nationally representative data on IPV prevalence in the United States finds that 24.3 percent of women and 13.8 percent of men experience “severe IPV” (see Figure 1).[9] Nearly half of U.S. men and women report experiencing psychological aggression, such as humiliating and controlling behaviors.[10] A study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) also found that 55 percent of murders of women were related to IPV, significantly more than the 16 percent that occurred at the hands of strangers.[11] Women also have experiences with IPV early in their lives, with young women at highest risk.[12]

Root Causes and Social Determinants of Health

Gender inequality (and the unequal power structures that underpin it) is the most consistent predictor of higher levels of violence against women at the population level.[14] This is often referred to as the root cause of IPV and explains its gendered patterns. Determinants of violence may present through attitudes condoning violence and/or rigid gender norms that vary across cultures but are still prevalent within modern societies.

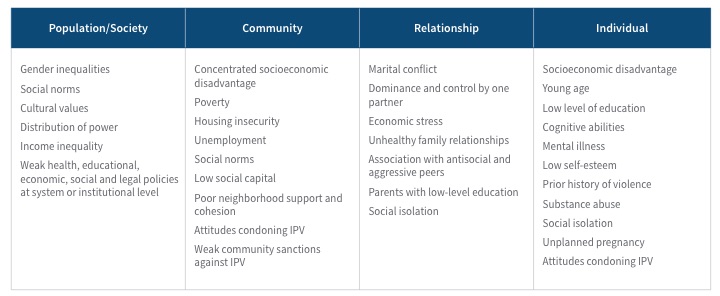

Given the nature of IPV, the social determinants of health can be analyzed within the context of the circumstances in which people live (such as their education, occupation, income, gender) and the broader context of economics, social policies, the political environment, cultural norms and health systems.[15] This is referred to as the “social ecological model” in public health, and it conceptualizes IPV as the result of the interplay between individual, relational, community and structural factors.[16]

Table 1 highlights several risk factors of IPV within this model that can influence health outcomes and behaviors. Some examples include socioeconomic disadvantage, low levels of education and employment, housing insecurity and social isolation, all of which can operate at both individual and community levels.[17] These risk factors themselves do not necessarily lead to greater levels of violence, but they become important when gender inequalities exist. Consequently, vulnerable populations are at higher risk, with women of color, indigenous, LGBT, disabled and migrant communities disproportionately affected by IPV.[18]

Table 1

Social Ecological Model and Risk Factors of IPV

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/riskprotectivefactors.html.

Another misconception about IPV is that it relates only to isolated incidents and stems from the inability to control anger. On the contrary, IPV is often displayed as a pattern of harmful behavior designed to dominate and control a partner.[19] The problem is insidious, hidden and complex. The silence and secrecy are enabling features of IPV. Women are also most at risk of severe harm when they try to leave abusive relationships.

IPV During COVID-19—The Shadow Pandemic

IPV has been coined the “shadow pandemic” during the global COVID-19 pandemic.[20] This has been a time when situational stressors such as financial stress, unemployment, social isolation and an inability to seek help safely has intensified experiences of IPV in many countries.[21] Part 2 of this article looks at the nature and impact of IPV during COVID-19.

Health and Economic Consequences of IPV

The long-term health impact for people exposed to IPV is severe.[22] In the United States, approximately 41 percent of women and 14 percent of men who are exposed to IPV sustain some form of physical injury related to it. In Australia, studies comparing the health burden of IPV (measured using disability-adjusted life years) with other risk factors have found that IPV contributes the most to the health burden in women aged 18–44 years.[23]

A causal relationship has also been found between IPV and the following health conditions:[24]

- anxiety,

- depression,

- suicide and self-inflicted injuries,

- alcohol-use disorders,

- homicide and violence,

- early pregnancy loss and

- complications resulting from premature and low-birth-weight babies.

There are also many other adverse health outcomes associated with IPV, including a range of cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, reproductive, musculoskeletal and nervous system conditions, many of which are chronic in nature.[25]

Given the myriad health conditions associated with IPV, it is unsurprising that women who experience it have higher health care service utilization and health care costs.[26] U.S. health insurance claims data analysis shows annual health care utilization is higher for all categories of health service—mental health, alcohol/drug, inpatient admissions, hospital outpatient visits, emergency department visits—when women experience IPV (compared to women without IPV exposure) and is still 20 percent higher five years after the abuse has ceased.[27]

Health care claims costs are 19–60 percent higher for women who experience IPV.[28] The variation depends on the type of abuse and time since abuse exposure. A statistically significant cost differential persists even after controlling for comorbidities and other confounders.[29]

The estimated economic cost of IPV was nearly $3.6 trillion (2014 USD) over the lifetime for U.S. adults with a history of IPV—this equates to $103,767 per woman and $23,414 per man.[30] Approximately 59 percent is for medical costs, and government sources pay 37 percent.

The estimated economic cost of IPV was nearly $3.6 trillion (2014 USD) over the lifetime for U.S. adults with a history of IPV—this equates to $103,767 per woman and $23,414 per man.[30] Approximately 59 percent is for medical costs, and government sources pay 37 percent.

How Can We Move Toward a World Free of IPV?

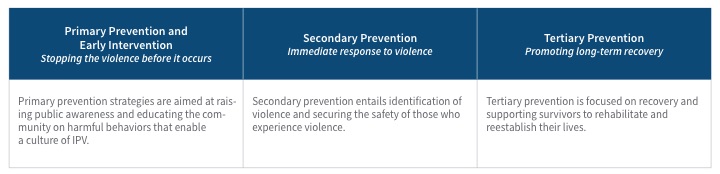

This is a big question, and there is much to do. For now, we summarize the public health model that is being used to eliminate IPV. The model, while originally designed to address disease prevention, has been adapted for use in the context of IPV.[32] The levels of violence prevention are categorized as primary, secondary and tertiary in Table 2.

Table 2

Public Health Model for IPV Prevention

We emphasize that like many other public health problems, the solution requires a deep-rooted, multisectoral approach with intensive, widespread and sustained action. Multidisciplinary research and analysis are also required to fill knowledge gaps and inform laws, policy and strategies to support prevention and response initiatives.[33]

What Can Actuaries Do?

We believe the actuarial community has a part to play in ending IPV for every person.

First, and most importantly, we all have a role within our own lives. Making meaningful and sustained changes in our families, workplaces and communities at large is an important first step.

Second, we have a unique skill set to help inform the response. Actuarial risk assessment tools are being used to assess for the risk of IPV[34] and recidivism of violence using information from policing.[35] People who are escaping violence often need financial support and employment. Multidisciplinary research is needed, particularly for vulnerable communities. The health burden and costs from both insurance and government perspectives are significant, but actuaries are experts at using data to provide advice on how costs can be reduced and outcomes can be improved.

To this end, the SOA Public Health IPV working group has planned three phases of work:

Phase 1: Education, raising awareness and information sharing within the actuarial community through a series of papers, webinars and podcasts.

Phase 2: A continuation of Phase 1 but with a focus on data collection and specific areas of need to provide insight into actions and further research.

Phase 3: Development of ideas and identification of areas of need to build research projects within the actuarial community.

There is much we can do as a profession to drive change for future generations. We encourage all those interested in being a part of this to get in touch.

Jananie William, FIAA, PhD, is a Senior Lecturer in Actuarial Studies at the Australian National University and Advisor to the Social Outcomes Lab. She can be reached at jananie.william@anu.edu.au.