Intimate Partner Violence: The Shadow Pandemic Part 2: Intimate Partner Violence During the COVID-19 Pandemic

By Nikita Chaudhry and Jananie William

Health Watch, March 2021

Editor’s note: This paper discusses experiences of violence which some readers may find distressing. Names in stories have been changed or withheld to protect the identity of the victims. Statements of fact and opinions expressed herein are those of the individual authors and are not necessarily those of the Society of Actuaries, the editors, or the respective authors’ employers.

In part 1 of this article, we presented background information on the global epidemic of intimate partner violence (IPV). This article discusses the surge in IPV during the COVID-19 pandemic, the resources available to victims during the pandemic and recommended priorities to support victims as we look toward a future free of IPV.

How the COVID-19 Pandemic Created the Perfect Storm for IPV

As of February 2021, there have been more than 2.4 million deaths globally and nearly 500,000 deaths in the United States due to COVID-19.[1] In response, many countries enacted stay-at-home orders to reduce the spread of the virus.[2] While these orders were implemented differently by jurisdiction, in most cases individuals were expected to isolate in their homes except for essential activities.

Governments introduced these measures ostensibly for public health reasons. However, an unanticipated side effect was to exacerbate violence experienced by victims of IPV, who found themselves trapped in isolation with their abusers, unable to see their family and friends or seek appropriate care. It is becoming clear that the forced quarantine has created a “perfect storm” for this type of domestic violence (DV) to thrive.[3] (Domestic violence is a term used to describe different types of violence within the family setting. This includes IPV as well as violence against children and elders. This article focuses on IPV, but DV resources are offered to all victims.)

Impact Across the World

Early reporting suggests that there has been a significant uptick in IPV incidence worldwide creating a “shadow pandemic”[4] during COVID-19. In response, in April 2020, the United Nations (UN) Secretary General António Guterres wrote:

Peace is not just the absence of war. Many women under lockdown for #COVID19 face violence where they should be safest: in their own homes. Today I appeal for peace in homes around the world. I urge all governments to put women’s safety first as they respond to the pandemic.[5]

The UN also reported significant increases in call volumes to DV hotlines in several countries: in Lebanon and Malaysia, call volumes doubled; and in China, they tripled compared with the same time last year.[6] Further reporting by individual countries emphasized the scale of the problem. The UK’s largest domestic abuse charity, Refuge, reported a 700 percent increase in calls to its helpline in a single day, while a separate helpline for perpetrators seeking help to change their behavior received 25 percent more calls after the start of the COVID-19 lockdown.[7] In India, the National Commission for Women saw reports almost double in the first three weeks of lockdown compared with the month leading up to it.[8] France, Brazil and Italy have also indicated substantial increases, and reports have surfaced of a horrific domestic violence-related homicide in Spain.[9]

The UN also reported significant increases in call volumes to DV hotlines in several countries: in Lebanon and Malaysia, call volumes doubled; and in China, they tripled compared with the same time last year.[6] Further reporting by individual countries emphasized the scale of the problem. The UK’s largest domestic abuse charity, Refuge, reported a 700 percent increase in calls to its helpline in a single day, while a separate helpline for perpetrators seeking help to change their behavior received 25 percent more calls after the start of the COVID-19 lockdown.[7] In India, the National Commission for Women saw reports almost double in the first three weeks of lockdown compared with the month leading up to it.[8] France, Brazil and Italy have also indicated substantial increases, and reports have surfaced of a horrific domestic violence-related homicide in Spain.[9]

Impact in the United States

Nature of IPV During COVID-19

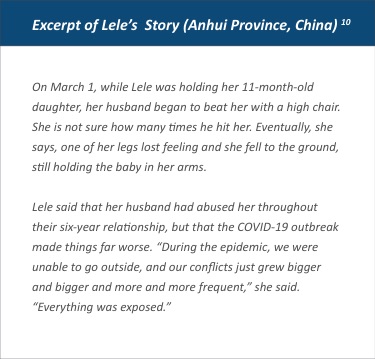

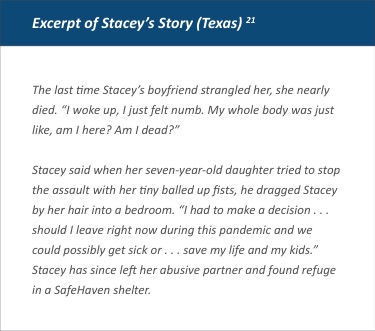

Mirroring the trends in the rest of the world, there has been an increase in calls to DV hotlines and police departments in some regions across the United States.[11] There are several reasons for the intensification of IPV during COVID-19. Situational stressors such as increased unemployment, social isolation and fewer avenues from which to seek help safely[12] (due to stay-at-home orders and social distancing measures) have escalated the impact of the violence. There are also reports that perpetrators have been using specific features of the pandemic to further abuse their partners; for example, victims having their stimulus checks taken away by abusers and abusers threatening to bring the COVID-19 virus home as a way of punishing the victim and children.[13] There is also a significant increase in the purchase of guns, which are being used to terrify the victims.[14] Research shows that access to a gun makes it five times more likely that a domestic abuser will kill their victim.[15]

“My husband won’t let me leave the house,” a victim of domestic violence, tells a representative for the National Domestic Violence Hotline over the phone. “He’s had flu-like symptoms and blames keeping me here on not wanting to infect others or bringing something like COVID-19 home. But I feel like it’s just an attempt to isolate me.”[16]

Resources Available to IPV Victims Prior to the Pandemic

The 1994 Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) is the first U.S. legislation to acknowledge DV as a crime and provide federal funding to fight it. Through this act, several legal assistance programs have been created for victims. In addition, victims are urged to call the national or state hotlines and seek safety at a DV shelter.

A 2019 survey conducted by the National Network to End Domestic Violence (NNEDV) estimated there are 1,887 violence programs in the United States; however, many of these are weak and underfunded. The NNEDV survey also estimated 11,336 unmet requests per day for housing and emergency shelter from survivors of IPV in 2019, prior to the pandemic.[17]

Resources Available to IPV Victims During the Pandemic

Despite victims being trapped in their homes with their perpetrators due to lockdown measures, only a few states exempted people seeking safety from stay-at-home orders. Essential services such as health care providers and police resources were stretched thin trying to combat the pandemic, which resulted in a shortage of these resources for IPV victims. In cases where law enforcement was involved, often little action was taken because jails and inmate facilities were simultaneously trying to keep their populations low to avoid the spread of the infection. In addition, shelters that would ordinarily be accessible to victims were unavailable because they were being used as health care facilities to treat COVID-19 patients or were capping their capacity to maintain social distancing.

Government officials at all levels found themselves unprepared to deal with the new crises and rushed to find ways to help the victims. New York experienced a 15 percent increase in DV calls in March 2020 compared to the previous year and a 30 percent increase in April 2020.[18] In response to this, the New York State Council on Women and Girls set up a new task force to find innovative solutions to address the spike in DV during the pandemic, recognizing that the current situation requires flexibility and a willingness to move beyond the idea that a shelter is the only option for victims and survivors. The task force’s immediate recommendations included:[19]

- Building on the current technology capabilities to reach more survivors; for example, by adding permanent features such as a chat and text component to their DV hotline.

- Flexible funding methods to meet survivors’ needs as quickly as possible.

- Housing solutions beyond shelters for those seeking a safe place to live, encouraging housing choices that take into consideration a survivor’s desires and goals for themselves and their families. There is also increased federal funding to support victims navigating housing services during the pandemic.

In Chicago, Mayor Lori Lightfoot announced that a new city partnership with Airbnb would provide hotel rooms to people who need to flee a violent situation.[20] We have also seen this requisitioning of hotels for women’s shelters in both France and Italy.[21]

At the federal level, there was additional funding provided through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act and the Health and Economic Recovery Omnibus Emergency Solutions (HEROES) Act in 2020.[22] The CARES Act included $45 million to programs funded by the Family Violence Prevention and Services Act to provide emergency housing and shelter to DV survivors across the country and $2 million to the National Domestic Violence Hotline. The HEROES Act added $100 million for Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) programs, including $50 million to the Family Violence Prevention and Services Act, of which $2 million is designated for the National Domestic Violence Hotline.

At the federal level, there was additional funding provided through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act and the Health and Economic Recovery Omnibus Emergency Solutions (HEROES) Act in 2020.[22] The CARES Act included $45 million to programs funded by the Family Violence Prevention and Services Act to provide emergency housing and shelter to DV survivors across the country and $2 million to the National Domestic Violence Hotline. The HEROES Act added $100 million for Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) programs, including $50 million to the Family Violence Prevention and Services Act, of which $2 million is designated for the National Domestic Violence Hotline.

Efficacy of Measures and the Way Forward

There is an increasing body of evidence for the shadow pandemic, and we have outlined some of the measures taken at state and federal levels to address this in the current environment. However, it is unclear at this point what impact these measures are having, or, indeed, the order of magnitude of the problem. This is primarily driven by a lack of data, either from medical, law enforcement or insurance sources. There is a significant knowledge gap that needs to be addressed as a matter of urgency.

There is no clear end to the COVID-19 pandemic. Although it is fair to say that no one could have predicted the unprecedented restriction on movement over the last few months, it would be prudent to expect that we will see additional COVID-19-related lockdowns in the coming months or years, or future pandemics following a similar pattern to this one.

As a result, there is an immediate need for the following:

- Mitigation measures must continue to be rolled out country-wide, building upon and strengthening processes that were developed pre-pandemic;

- The community must ascertain the extent to which the pandemic is impacting instances of IPV and identify existing measures that have proven the most effective. This requires an analytical, data-driven approach.

- Policymakers need to proactively develop IPV-related measures to mitigate the impact of future stay-at-home situations. We must highlight the unique needs of vulnerable populations to be considered when developing these measures.

We are at a critical inflection point regarding IPV in the post-COVID-19 world. Immediate action is required to ensure that one health crisis does not worsen another. As outlined in part 1 of this article, we believe the actuarial profession has a part to play in the pursuit of ending IPV for all people. We have opportunities to use our unique expertise to develop a body of work that will support IPV prevention, intervention and recovery efforts during the pandemic and beyond. The ability to analyze the health and economic cost burden and potential benefits of existing and proposed IPV mitigation measures, especially in the context of COVID-19, is particularly pertinent in the current environment. We are keen to hear from members who are working in related areas as we explore areas of urgent need to which we can contribute.

Nikita Chaudhry, FSA, is a Senior Actuary at Ironshore. She can be reached at nikita.chaudhry@ironshore.com.

Jananie William, FIAA, PhD, is a Senior Lecturer in Actuarial Studies at the Australian National University and Advisor to the Social Outcomes Lab. She can be reached at jananie.william@anu.edu.au.