The Potential of Infra-Low Frequency Neurofeedback to Reduce Medical Claim Costs and Dramatically Improve Patients’ Lives

By Charles T. Doe and Matthew Fleischman

Health Watch, July 2023

Note: Some of the information in this article and related data analysis has been taken from the Neurofeedback Advocacy Project website that was created by Matthew Fleischman.

Group health actuaries may find a 2011 study on the effective treatment for people suffering from schizophrenia to be very interesting given the implications for reducing high mental health care costs.[1] The study successfully used neurofeedback to treat almost 150 chronic cases of schizophrenia that had been resistant to years of inpatient medical and psychological treatment. A two-year follow-up found that positive changes were sustained, and it documented clients’ continued satisfactory adjustment with stabilization using less than one half the number and dosage of medications in comparison with the onset of treatment.

Neurofeedback is an intervention that has significant implications for lowering mental health care costs. It has been shown to be effective for a number of behavioral health–related challenges, including complex mental health conditions like addiction and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Combined results from various websites suggest that more than 40 different conditions have been helped by neurofeedback. The goal of this article is to present clear evidence that neurofeedback has a high probability of reducing health care costs for many mental health conditions. We will provide documentation of (1) the significant reduction in symptoms of patients given 20 sessions of infra-low frequency (ILF) neurofeedback, including numerous improvements in various behaviors such as self-harm/suicidal ideation; (2) a significant reduction in the use of medical care services for psychiatric conditions; (3) self-harm/suicidal ideation data broken out by age and gender; (4) an estimate of the gross per member per month cost of neurofeedback; and (5) insurance companies and government entities that cover neurofeedback.

Neurofeedback is a form of brain training to improve functioning. ILF neurofeedback employs both higher frequency brain waves and extremely low-frequency brain waves.[2] Neurofeedback is a safe, noninvasive and nonverbal approach. It works by engaging the brain’s own mechanisms of self-regulation. Neurofeedback is not about learning to relax. The client is instructed not to try to do anything beyond attending to the process. ILF neurofeedback protocols are based on symptoms and history, not diagnoses.

Efficacy of ILF Neurofeedback

There are several different ways to answer the question of whether ILF neurofeedback is successful in treating behavioral health conditions. We will provide a few of these different answers.

The Neurofeedback Advocacy Project (NAP) was created to help provide access to ILF neurofeedback training and equipment to behavioral health clinics that deliver mental health services to the underserved and most vulnerable in Oregon. As part of the NAP and based on his 30 years of experience with neurofeedback, Matthew Fleischman developed the Results Tracking System (RTS) in 2018. The goal of the RTS was to gather data on clients receiving ILF neurofeedback and provide documentation of the expected material reduction in symptoms that clients were living with based on their self-assessments. The data produced by the RTS are presented in the charts in this section.

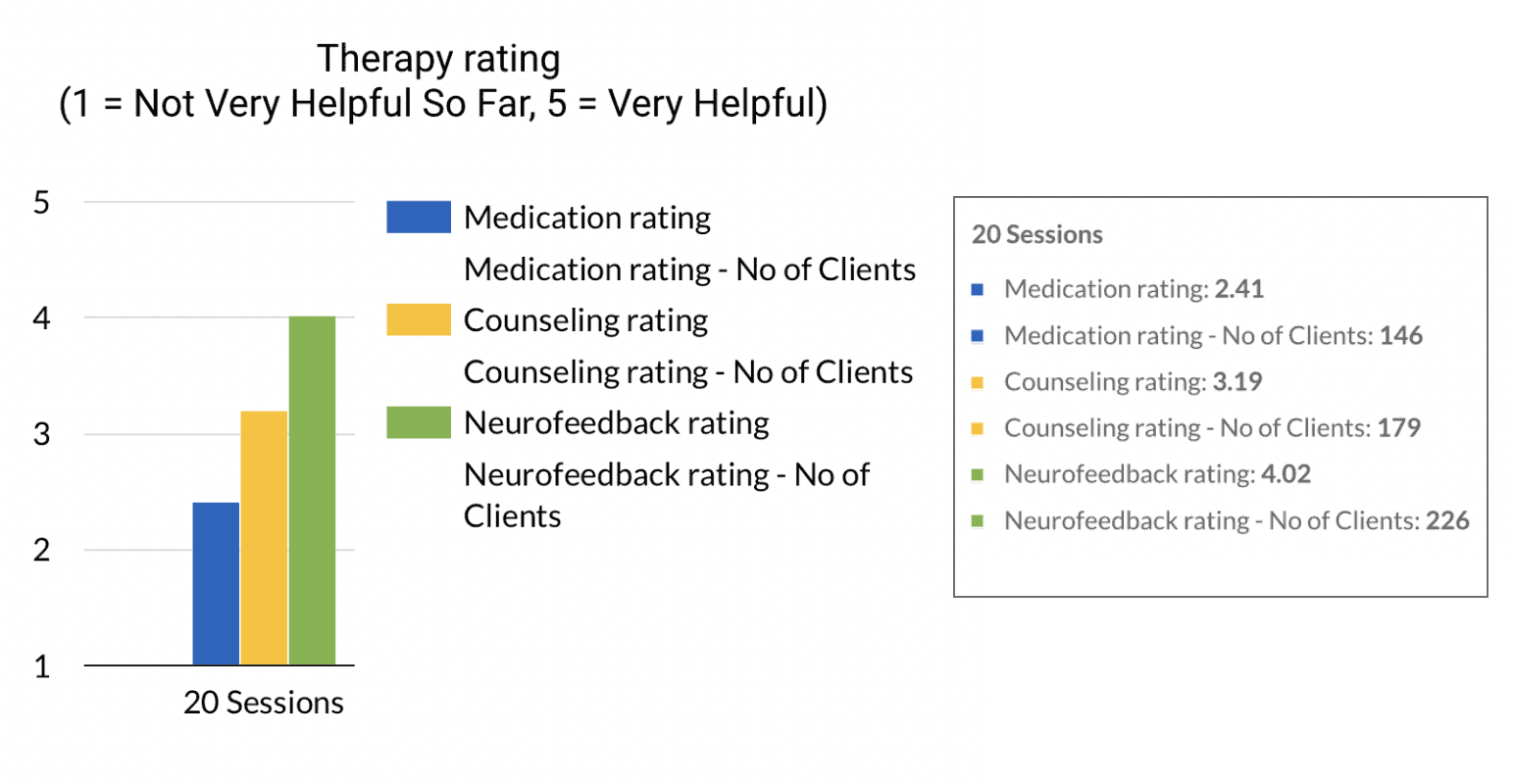

Client therapy rating data show that clients strongly favor ILF neurofeedback over counseling and medication (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Therapy Ratings by Clients

The number of agencies and therapists providing ILF neurofeedback as part of the project has grown dramatically in the last year and should continue this growth into the future. As a result, there are expected to be similar increases in the number of clients that will have received at least 20 sessions by this time next year. This continued growth in both therapists and client counts in the future will probably result in more than 1,000 clients receiving 20 sessions by mid-2024 versus more than 440 as of May 2023.

Another way of looking at the success of ILF neurofeedback is to look at the no show/late cancellations (NSLC) percentage (Figure 2). The fact that this number is only 2 percent, based on thousands of scheduled ILF therapy sessions, is perhaps one of the most significant validations of ILF neurofeedback. The result for adults alone is 1 percent. In comparison, nearly all online reports indicate that no show rates vary from 10 to 30+ percent for behavioral health visits. That neurofeedback produces rapid improvement, does not require a discussion of painful topics and mainly involves watching videos or playing video games is certainly part of its appeal. That it reduces the adverse symptoms clients have often suffered with for years or decades is another.

Figure 2

No Show/Late Cancellations for ILF Neurofeedback Therapy (May 2023)

ILF neurofeedback is used in dozens of countries around the world and by more than 5,000 neurofeedback therapists, with over several hundred new therapists trained every year. This suggests that 100,000 to 200,000 people annually receive 20 to 30+ sessions of ILF neurofeedback, assuming a therapist provides 10 to 20+ sessions per week for 40 weeks on average. The continued use by professionals around the world and the number of therapists being trained should also be considered another validation of the effectiveness of ILF neurofeedback.

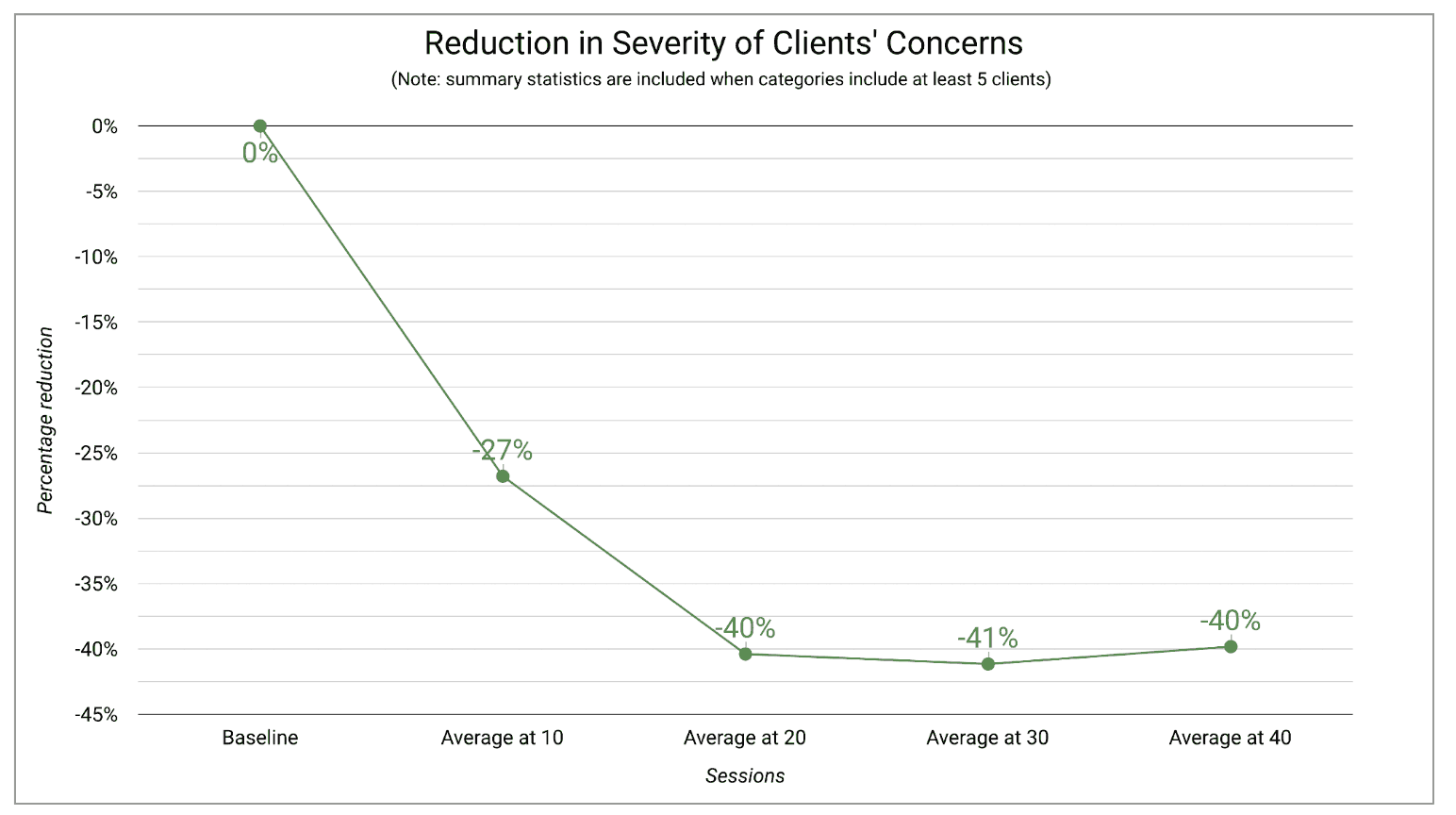

A 40 percent reduction in symptoms for more than 450 clients as a result of 20 sessions of ILF neurofeedback is another way of answering the question of whether this intervention is successful in treating behavioral health conditions. The symptom reduction results are based on clients’ own rating of five to eight symptoms that had the most adverse effects on their lives before and after 20 sessions. For the baseline, clients were asked to rate each concern on a 0 to 10–point scale for a “bad week,” a “good week” and a “usual week,” where lower numbers indicate the concern is less severe. The average of the three ratings was the baseline for each symptom. Once neurofeedback began, the clients were asked to make the same ratings at each session. A reduction in symptoms was calculated by averaging the ratings for each concern for the last three sessions.

Figure 3 reflects the percentage reductions in symptoms versus the baseline after X sessions, as already defined. The results are based on patients that have completed X sessions but less than X + 10 sessions.

Figure 3

Reduction in Symptoms after 10, 20, 30, and 40 Sessions

The NAP results page allows filtering by clicking on a part of the circles to the right of the graphs. The filtering data are based on demographics for clients who have completed 20 sessions. To refresh the data and remove all previously filtered data for a particular characteristic, click on the very small reset arrow that appears to the upper left of the large circle. Hovering over any data point provides the exposure numbers for the filtered data. The following characteristics may be used as filters: age groupings, gender, race/ethnicity, adverse childhood experiences (ACEs; 0 to 10), percentage on medication at baseline, child receiving services, number of DSM psychosocial stressors (0 to 10) and number of co-occurring disorders.

Certain data collection was added after the original creation of the results charts so the exposures outside of the main results chart are lower. The symptoms percentage decrease of the available graphical charts provide the percentage reductions versus the baseline results.

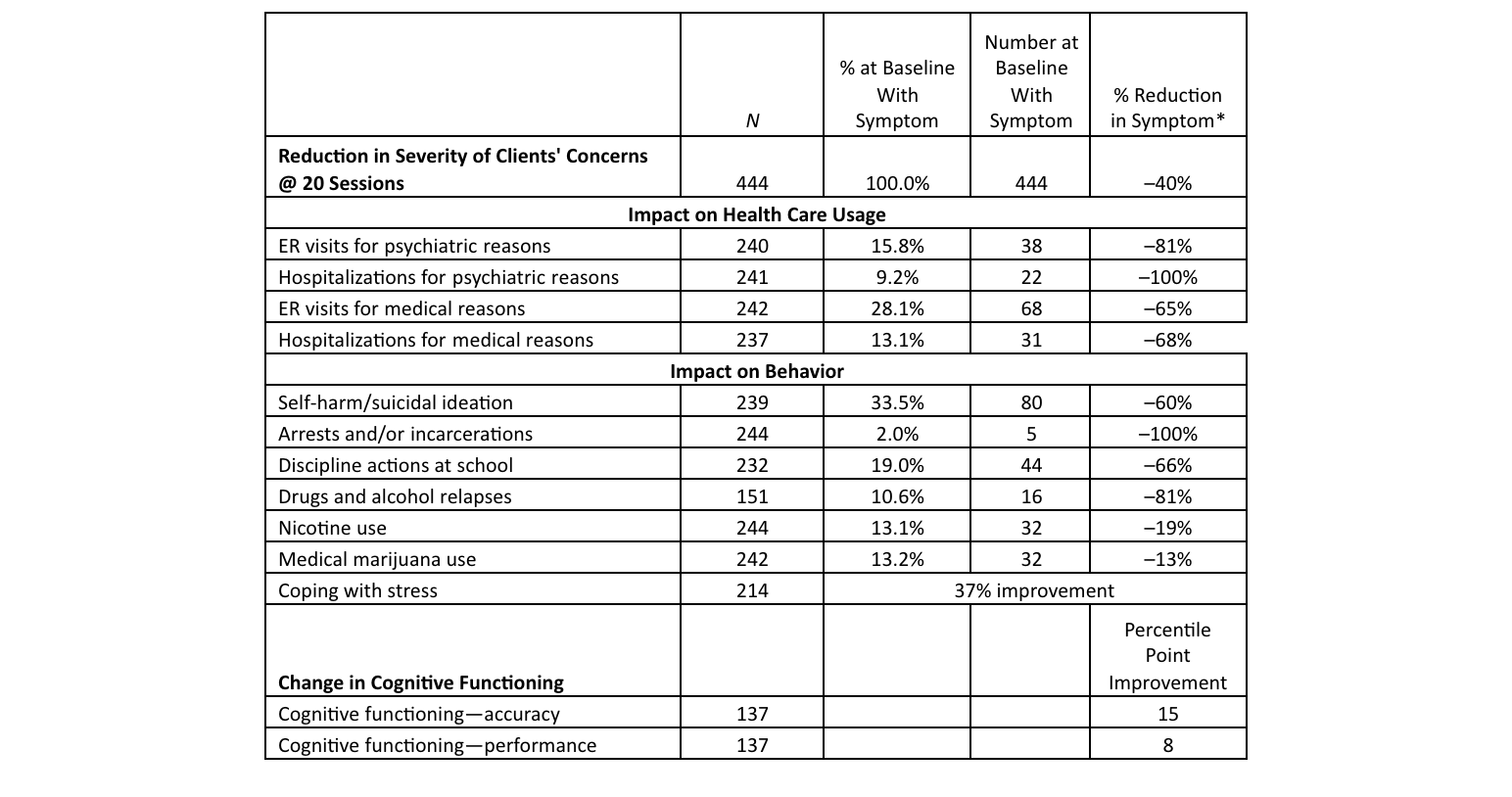

The results shown in Figure 4 are from the May 2023 update of data. The results are all very positive, but of special note is that ILF neurofeedback has produced around a 60 percent overall reduction in patients’ self-harm/suicidal ideation. Figure 4 was created by pulling the data from all the charts.

Figure 4

Symptoms Percentage Decrease

*Not annualized (discussed below).

A couple of interpretive issues need to be addressed. The definition of the baseline and the average of the results at the latest three sessions slightly underestimate the magnitude of the decrease in both symptoms and other measures.

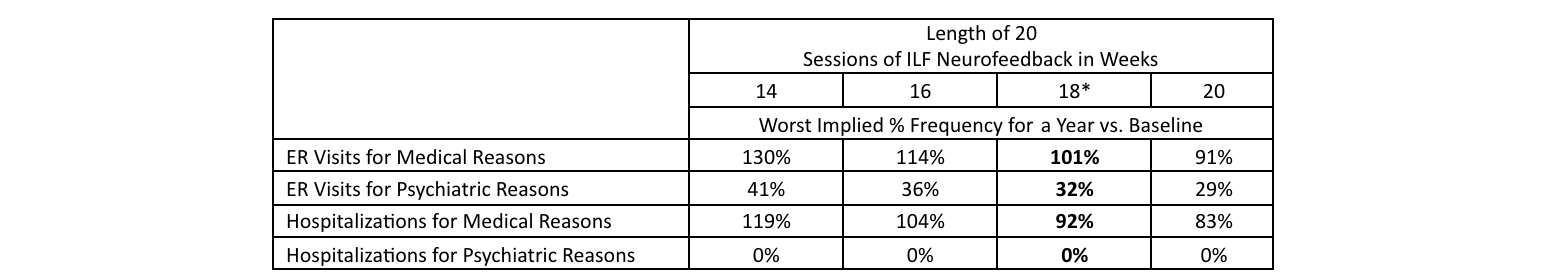

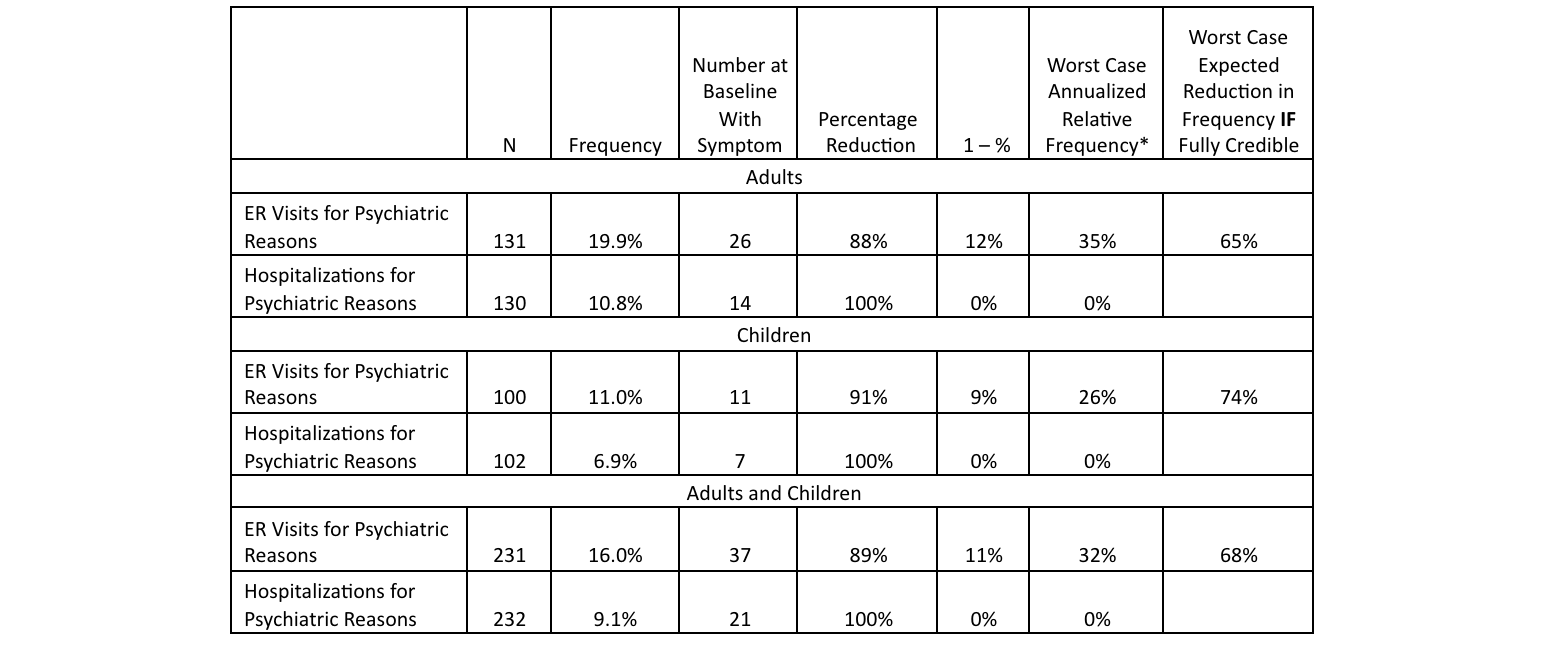

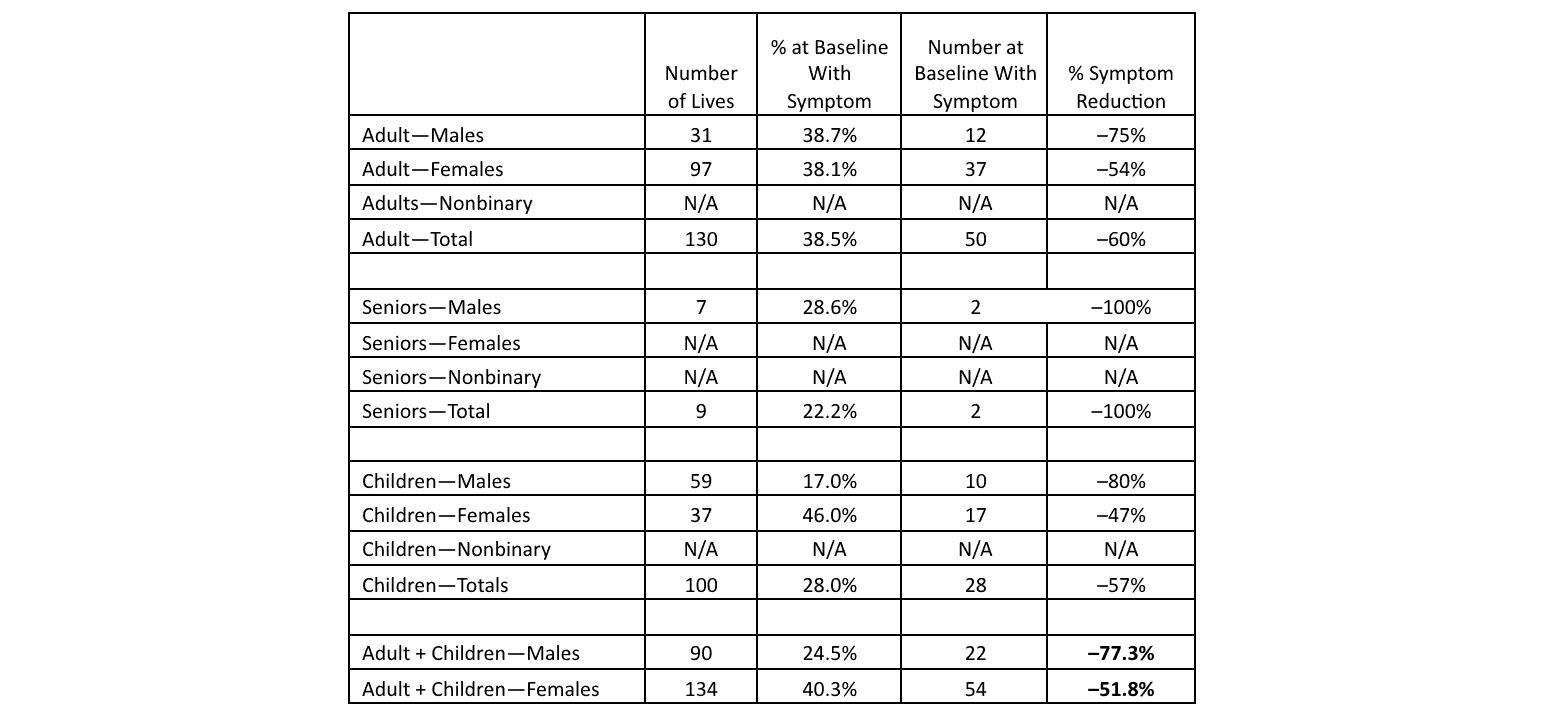

The relative frequencies after 20 sessions, i.e., 100 percent minus the percentage reduction in the use of emergency room and hospitalization, versus the baseline frequency represent the relative experience over the entire time period to complete 20 sessions. Therefore, the frequency is probably likely to represent the results on average after about 10 sessions, so further improvements are expected for this reason. The frequencies would also be expected to improve with more sessions. The data for the next 20 sessions are clearly needed to clarify the expected frequency over a longer period of time.

Assume that the reduction in the use of the emergency room is 80 percent, meaning the relative frequency is 20 percent. If that is over six months and not expected to improve in the next six months, the annual relative frequency would be 12/6 x 20%, or 40 percent of the baseline frequency. If the time period were for three months, the outcome would be 80 percent.

Figure 5 compares the relative frequencies for adults versus children through 20 sessions for emergency room visits and hospitalizations.

Figure 5

Interpreting NAP Impact on Health Care Usage Results

*18 is the estimate for the current data due to COVID.

Figure 6 compares the relative frequencies and expected reductions in usage for adults versus children through 20 sessions for emergency room visits and hospitalizations for psychiatric reasons.

Figure 6

Interpreting NAP Impact on Psychiatric Health Care Usage Results

*Estimated time to reach 20 sessions is currently 18 weeks so the (1 – %) column is annualized. Additional sessions up to 30 or 40 are expected to reduce this result further.

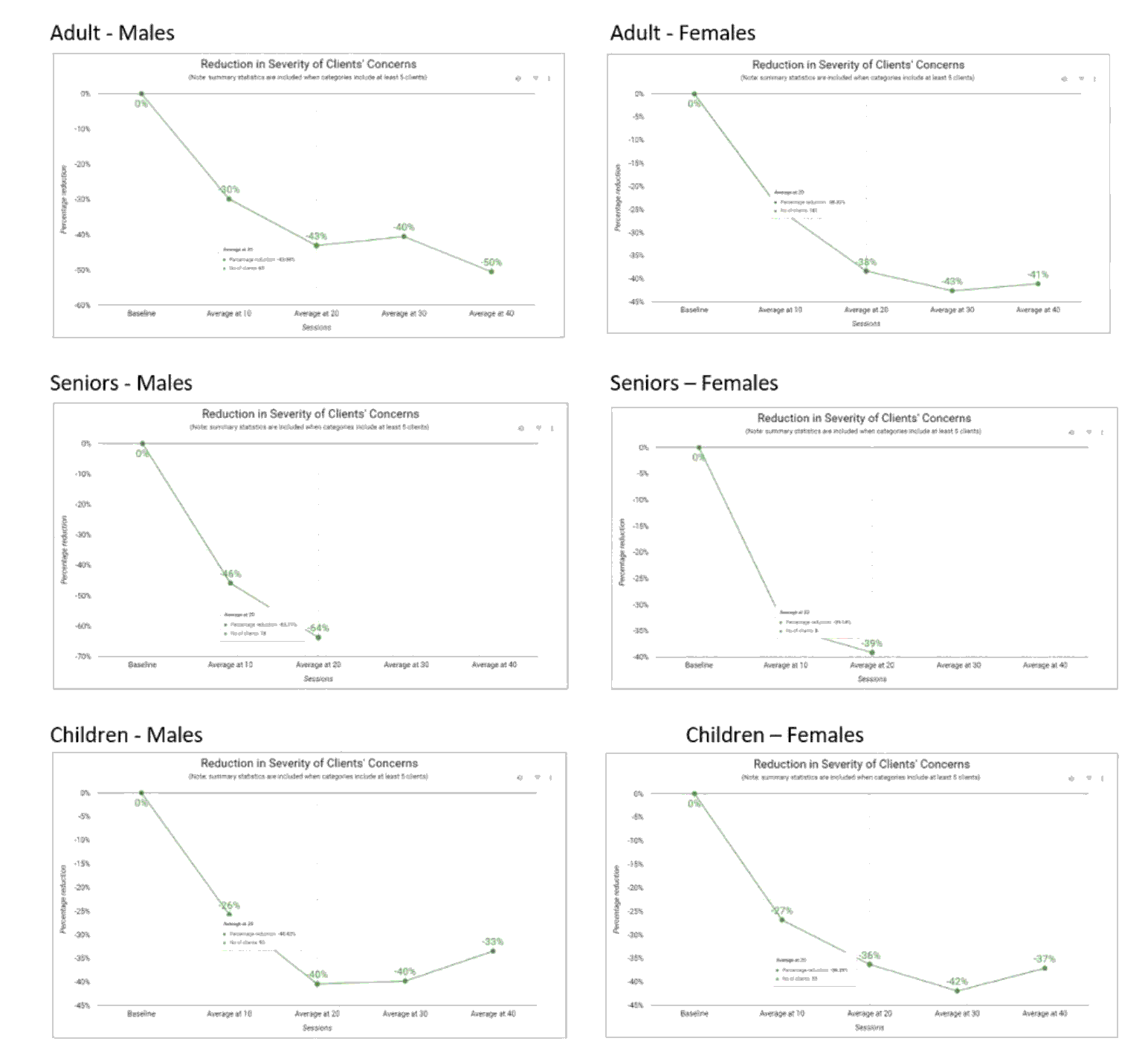

The charts in Figure 7 are examples of filtering to provide a better understanding of the data and the insights that can be gathered.

Figure 7

Reduction in Symptoms for Adults, Seniors and Children

The table in Figure 8 is a summary of filtering for each of the following categories for self-harm/suicidal ideation. The reduction for males excluding seniors after 20 ILF neurofeedback sessions is over 75 percent, and the reduction for females excluding seniors is over 50 percent.

Figure 8

Breakdown of Self-Harm/Suicidal Ideation Results

How ILF Neurofeedback Could Affect Health Care Costs

What are the implications for medical costs for Medicaid, Medicaid managed care products, group medical insurance products, Medicare Advantage products and potentially other products like short- or long-term disability for behavioral health disabilities? What if the average equivalent mental age of children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and other comorbidities could be increased by two years after 30 sessions of ILF neurofeedback to be consistent with their average age, as was concluded by an ILF neurofeedback study of almost 200 children?[3] What are the implications for individuals with PTSD when they no longer meet that diagnosis after receiving neurofeedback therapy, as was found for 60+ percent of those treated in a 2016 study (N = 52)[4] and a 2020 study (N = 36)[5], among others? What if the standardized mortality rate (SMR) for veterans with PTSD could be reduced by 20 percent from over 2.5 to 2.0 or even lower by substantially decreasing suicidal ideation?[6] What if the rates of suicide could be reduced for people dealing with addictions?

What should insurance carriers covering neurofeedback be doing to analyze the gross and net costs, i.e., the effectiveness of neurofeedback, when looking at cost savings over the one to three years after clients complete the therapy? What, if any, obligation do health insurance companies have to publish their data in order to promote greater acceptance of neurofeedback and dramatically reduce the adverse symptoms affecting too many people, as well as suicide rates?

Let’s look at a quick scenario of the possible gross per member per month (PMPM) costs based on the assumption that there are about 15,000 neurofeedback therapists in the country (perhaps a conservative estimate, given that a 2014 estimate was 10,000[7]), and 125 million out of the 156 million (80 percent) fully insured members in the United States had coverage for neurofeedback. Assume that neurofeedback costs $6,000 for 30 sessions and that deductibles and coinsurance reduced the cost on average by 60 percent. What would the maximum PMPM medical cost be, assuming the average number of neurofeedback sessions per therapist per year was 800 and each insured had 30 sessions?

- Maximum number of clients that could be treated = 15,000 × 800/30

- Estimated insurance cost = 15,000 × 800/30 × $6,000 × .6

- Maximum PMPM = 15,000 × 800/30 × $6,000 × .6 / (100,000,000/12) = $.96

This leaves us with a range of between $.50 and $2.00 or somewhat higher with more neurofeedback practices in some areas.

Frequently Asked Questions About Neurofeedback

To aid the public and insurers in determining whether neurofeedback is worth the cost, many providers of this therapy devote sections of their websites to answering common questions such as the following.

How Frequently Is Neurofeedback Therapy Usually Provided?

The best effects of neurofeedback are achieved when at least two weekly sessions are completed. While 20 to 40 neurofeedback sessions are usually needed for the results of to be permanent, some clients achieve substantial elimination of their symptoms more quickly, while some clients’ symptoms require more than 50 sessions, e.g., this can be true for patients with multiple traumas or schizophrenia.

What Is the Success Rate of Neurofeedback?

Published study success rates depend on a number of variables, including the type of neurofeedback used, the number of neurofeedback sessions provided, the training and experience of the neurofeedback provider overseeing the protocols being used, the symptoms being treated and the complexity of the symptoms. Several online sites suggest success rates between 75 and 80 percent. Input from several very experienced neurofeedback providers has indicated that they have achieved a success rate of over 90 percent, while one study showed a success rate of 97 percent for almost 200 children.[8]

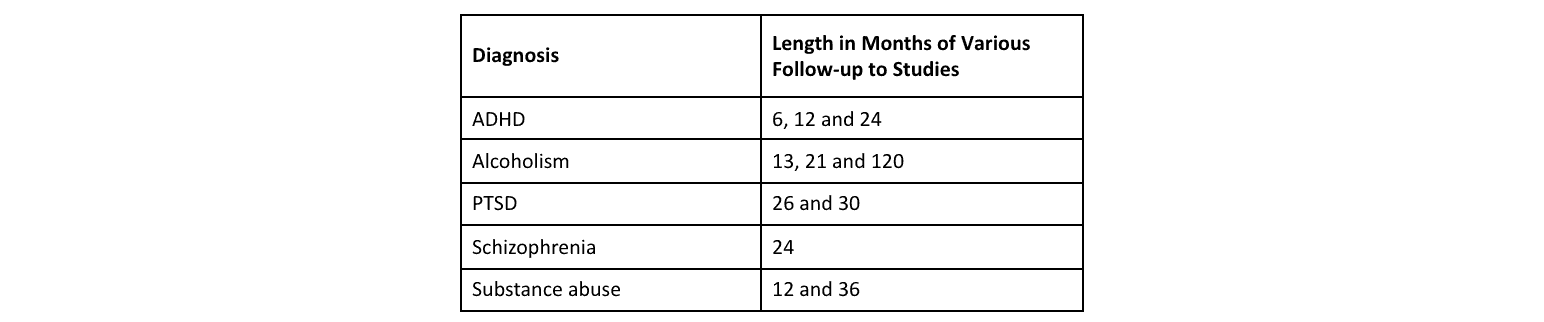

Are Results from Neurofeedback Sessions Permanent?

Figure 9 shows how many months of follow-up different studies used to determine that the successful results from the studies were maintained.

Figure 9

Follow-up Studies to Determine Permanence of Changes from Neurofeedback Therapy

Current Coverage of Neurofeedback Therapy in the United States

The current coverage by insurance companies and government agencies suggests that two or more companies could perform cost-benefit analyses for publication in the Health Watch newsletter or presentation at the Society of Actuaries annual health meeting. Other carriers that have more limited information could still provide valuable insights. Analysis that included claim per member per month costs for neurofeedback and an analysis of the net claim costs that included claim savings over one to three years would be extremely helpful in providing insights for all Medicaid risk insurers and group medical insurers.

The following insurance companies cover neurofeedback broadly at present and probably have for a number of years. Dates noted are those posted on the companies’ websites.

- Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan: has covered ADHD through age 18 since 2013 and for all ages since 2015–16[9]

- Centene Corporation: covers anxiety disorder or PTSD[10]

- Health Net of California (owned by Centene Corporation): covers generalized anxiety disorder, PTSD, or ADHD[11]

In addition, several online sources mention that more than 10 different insurance companies cover neurofeedback, which is likely in a very limited context rather than as a company-wide policy.

The following Medicaid entities cover neurofeedback based on online information (This list is not intended to be exhaustive.):

- California

- California Health & Wellness (Health Net of California), owned by Centene Corporation: covers generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), PTSD and ADHD[12]

- In support of the Pritzker Foster Care Initiative

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Kansas

- Sunflower Health Plan, owned by Centene Corporation[13]

- Louisiana

- Louisiana Healthcare Connections, owned by Centene Corporation: covers anxiety disorder and PTSD[14]

- Missouri

- Centene Corporation: covers anxiety disorder and PTSD[15]

- Nevada

- Centene Corporation (NV.CP.BH.300): covers attention deficit disorders, depressive disorders, bipolar disorders, obsessive compulsive disorders, oppositional defiant and/or reactive attachment disorders, PTSD and schizophrenia[16]

- Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield Healthcare Solutions: covers unspecified neurofeedback[17]

- New Hampshire

- Celtic Insurance Company, owned by Centene Corporation: covers acquired brain injury[18]

- Oregon

The following government entities have approved the use of neurofeedback as described here:

- The State of Texas has mandated coverage of acquired brain injury for about 15 years.

- NASA has used neurofeedback since the early 1970s for astronauts suffering from hallucinations, bouts of nausea and epileptic fits. Online information suggests that this still continues to some degree.

- The US Department of Veterans Affairs supports the use of biofeedback/neurofeedback modalities in the treatment of veterans if these modalities are supported by research and recognized by the major professional organizations in the field. The coverage is supported through Optum.[19]

- Veterans Affairs Canada has covered neurofeedback for a number of years. The current policy covers neurofeedback for several conditions—PTSD, GAD and major depressive disorder (MDD).[20]

Conclusions

Several conclusions can be drawn from the NAP RTS information we have studied here:

- The expectation is that continued improvement in symptoms and medical costs after 20 ILF neurofeedback sessions will often occur when clients undergo another 10 to 20 sessions; thereafter, there may still be some degree of improvement.

- ILF neurofeedback has a high probability of reducing suicides, but the data indicate that females have greater challenges in reducing their self-harm/suicidal ideation symptoms (50 percent) when compared with males (75 percent), both excluding seniors. Filtering the data provides material insights into the results.

- Potential cost savings other than the medical costs for emergency room visits and hospitalizations include the expected savings from fewer office visits, prescription drugs, short-term disability claims and potentially long-term disability claims, as well as lower mortality rates. Other possible impacts to consider would be fewer missed days in the office and the longer-term implications of fewer addictions.

- Twenty sessions of ILF neurofeedback have contributed to a material increase in cognitive functioning, which data suggest will likely lead to improved performance in school, fewer disruptions in the classroom, fewer children being bullied, improved workplace performance, fewer mental health days off from work, a happier home life for the entire family, probably fewer divorces and other societal benefits like fewer people on welfare or going to prison.

- Some companies seem to have concluded that providing coverage for neurofeedback for certain conditions is both beneficial to insureds and likely to reduce medical costs (or at least not add to costs).

- Clients on a substantial and rapidly growing exposure have seen significant long-term reductions in adverse symptoms that would benefit the broader population if neurofeedback were covered by insurance companies.

- Continued analysis of emerging results from the Neurofeedback Advocacy Project and potential industry data should provide additional insights into and higher credibility for neurofeedback as an efficacious intervention. Such results may improve the potential of some group health insurance companies adding neurofeedback coverage for their own employees or certain segments of their business, such as large groups where the risks are shared or fully absorbed by the employers.

- Additional ongoing research on neurofeedback by members of the Society of Actuaries is essential to an enhanced understanding by key decision makers in the group health insurance industry.

Resources

If you are interested in more background on the Neurofeedback Advocacy Project, it can be found on the NAP website, including a 2022 article by Matthew J. Fleischman on the impact of ILF neurofeedback on underserved populations.

Experience studies for ILF neurofeedback filtered by condition is available from the EEG Institute.

Recommended reading includes two books:

- The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma by Bessel van der Kolk. Chapter 9 is on neurofeedback. Many readers, some with a history of trauma and even those without, have found the book very informative.

- Conquering Concussion—Healing TBI Symptoms with Neurofeedback and without Drugs by Mary Lee Esty. Chapters 1 through 5 provide an excellent explanation of the numerous issues associated with mild to moderate concussions and some more significant head injuries. Chapters 6 through 9 and 12 provide a number of exceptional examples of recovery from concussions.

You are also encouraged to watch a video interview with Mary Lee Esty, Ph.D., that includes four dramatic cases treated successfully with neurofeedback.

Statements of fact and opinions expressed herein are those of the individual authors and are not necessarily those of the Society of Actuaries, the editors, or the respective authors’ employers.

Charles T. Doe, FSA, MAAA, is a retired group health actuary. Charlie can be reached at charlie.doe26@gmail.com.

Matt Fleischman, PhD, is the director of the Neurofeedback Advocacy Project. Matthew can be reached at matt6080@icloud.com.