The Run-Away 340B Drug Subsidy Program

By Tony Pistilli

Health Watch, March 2023

I chuckled when I read the recent Supreme Court opinion in American Hospital Association v. Becerra[1] that centered on the federal government’s 340B program, which allows providers participating in the program to purchase drugs from manufacturers at mandated steep discounts. Providers can charge the full, undiscounted price for 340B drugs to most patients, which means the provider retains the amount of the 340B discount as profit. Some providers qualify for 340B because of the type of facility they are (e.g., critical access hospitals). Others qualify for the program by demonstrating that a substantial component of the care they provide is to indigent and medically needy populations; the 340B retained margins are intended to offset uncompensated care provided to those populations.

The American Hospital Association (AHA) challenged a U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) rule that, in effect, required a provider to charge Medicare patients the discounted price the provider paid for the drug plus a small administrative/acquisition fee (though the legal basis of the case was somewhat more nuanced). This rule resulted in a significant decrease in revenue and profits for 340B-qualified facilities. In defending the rule, HHS argued that “Congress could not have intended for the agency to ‘overpay’ 340B hospitals for prescription drugs,” but the opinion dryly retorted, “Congress was well aware that 340B hospitals paid less for covered prescription drugs,” concluding that HHS’s rule was unlawful. I’ll leave it to the reader to decide how aware Congress may be.

History of 340B

The 340B program takes its name from Section 340B of the Public Health Service Act,[2] which—when enacted in 1992—was designed to remedy an unintended consequence of the 1990 enactment of the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program (MDRP). The MDRP required pharmaceutical manufacturers to enter into a mandatory Medicaid rebate agreement with HHS as a condition for coverage of their drugs by Medicaid and Medicare Part B.

For generic drugs, the mandatory minimum rebate is 13 percent of the average manufacturer price (AMP). For brand drugs, the mandatory minimum rebate is the greater of 23.1 percent of AMP or the difference between AMP and the manufacturer’s “best price.”

AMP approximates the price at which pharmacies and wholesalers can purchase the drug and does not include rebates negotiated with pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs). The Medicaid best price does include rebates, so for drugs offering a significant rebate, the MDRP mandatory rebate is greater than the 23.1 percent because the difference between AMP and the Medicaid best price is larger than that of the minimum mandatory rebate amount. 340B prices are not publicly available, but the Government Affordability Office (GAO) estimated 340B discounts at 20 percent to 50 percent in 2011[3]—the upper end of that range has likely risen significantly in the last decade.

There is also an inflation penalty that increases the mandatory rebate by the amount of a drug’s price increase in excess of the urban Consumer Price Index adjusted for inflation. This inflation penalty is sometimes referred to as “penny pricing,” because manufacturers can pay a mandatory rebate equal to the full price of drugs whose prices have increased significantly since initial launch.

Before the passage of the MDRP in 1990, pharmaceutical manufacturers would supply their drug products at a discount to providers and pharmacies serving indigent and medically needy populations as a form of charity. The MDRP caused manufacturers to end many of these arrangements because these privately agreed discounted rates could constitute their Medicaid best price, requiring them to provide the same discounts in the form of mandatory rebates to all Medicaid patients. As a result, providers who had historically purchased drugs at a discount were forced to pay full price.

Congress passed 340B to remedy this unintended consequence of the MDRP. 340B established criteria by which certain types of providers were designated “covered entities” and allowed these entities to purchase drugs at a discount equal to the Medicaid mandatory rebate. In exchange, payers cannot receive the Medicaid mandatory rebate for drugs purchased through the 340B program (doing so would “double-dip” on the discount amount). A manufacturer’s net revenue for a Medicaid patient who received a drug through 340B or outside of 340B would be similar, though in the former instance, the manufacturer receives a lower list price in revenue, and in the latter the manufacturer receives the full list price in revenue but pays a mandatory rebate.

The 340B program applies to all of a covered entity’s patients, not just those covered by Medicaid or who are otherwise needy. Covered entities can purchase drugs at the 340B discount regardless of the insurance coverage or financial need of the individual patient because the entities qualify based on the characteristics of the total population they treat. There are two main ways to qualify as a 340B covered entity. The first is based on facility type, meaning certain types of clinics and health centers, such as federally qualified health centers, Indian health centers, Title X family planning clinics, critical access hospitals, Ryan White programs and comprehensive hemophilia diagnostic treatment centers. The second way allows hospitals with certain organizational designations that serve a certain percentage of Medicaid or indigent patients to be 340B eligible. These types of hospitals include “disproportionate share hospitals” (DSH), as well as children’s hospitals, freestanding cancer hospitals and sole community hospitals. The exact disproportionate share calculation varies with hospital location, number of beds and inpatient care revenues.[4] Currently, 43 percent of acute care hospitals are 340B qualified and provide 75 percent of Medicaid hospital services.[5]

In 2010, the Health Resources and Services Administration (the division of HHS responsible for managing the 340B program) issued a rule that clarified that 340B covered entities may elect to designate a contract pharmacy to dispense 340B drugs on their behalf.[6] These arrangements may be helpful for covered entities that do not manage their own pharmacies or whose pharmacy services are not able to provide all drugs (for example, drugs with limited distribution channels and special storage requirements).

Contract pharmacies may charge an administrative fee for each prescription they administer on behalf of a 340B covered entity. These administrative fees may be a flat fee, a percentage of the amount charged for the drug or a percentage of the 340B margin (the gap between the full list price and the 340B discounted price). These fee arrangements were outlined in the GAO report mentioned earlier; however, the exact terms of these contracts are not publicly available.

340B Financials

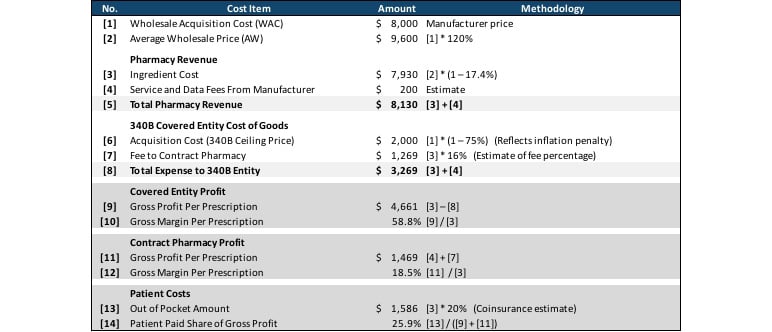

Table 1 summarizes the complex economics of 340B purchasing and reimbursement. In this example, the 340B covered entity purchased a drug with a wholesale acquisition amount (WAC) of $8,000 ([1]) at the 340B acquisition price of $2,000, reflecting the mandatory rebate and an inflation penalty. The pharmacy charged the member the normal non-340B price of $7,930 ([3]), which it passed on to the 340B covered entity minus a 16 percent fee to the covered entity for providing services as a contract pharmacy [7]. The pharmacy also received $200 in service and data fees from the drug manufacturer, which it retained.

In total the covered entity profited $4,861 ([9]) from the nearly $6,000 gap between the $7,930 ([3]) that was charged for the drug and the $2,000 ([6]) for which the drug was purchased. The contract pharmacy had a profit of $1,469 from retaining 16 percent of the drug charged amount ($7,930, [3]) and the $200 service and data fee from the manufacturer. The member’s out-of-pocket amount of $1,586 represented 25 percent of these profits, while the remaining 75 percent came from the manufacturer discount.

Table 1

340B Economics: Profits of Covered Entity and Contract Pharmacy, and Costs to Patient

This example shows the significant profit both the covered entity and the contract pharmacy can achieve when dispensing 340B covered drugs and highlights one of the key concerns that critics of the 340B program have. In all scenarios, the commercial-insured member in this example paid over $1,200 out of pocket for the prescription, and the commercial payer paid the remainder of the $4,956 ingredient cost for a drug the pharmacy purchased for $1,250. This may seem to contradict the 340B program’s goal of increasing access to drugs for indigent and medically needy populations, because while the margin the 340B covered entity retains from this transaction can be used to offset under-reimbursed care provided to other patients, the patient in this specific transaction is not indigent or medically needy, and there is no clear mechanism for the significant bump in gross profit that the contract pharmacy receives to be redirected to the indigent or medically needy.

Growth in the 340B Program

The 340B program has grown significantly since it started in 1992. Total purchases through this program grew from $2.4 billion in 2005 to $38.0 billion in 2020,[7] a 20.2 percent annual increase, significantly outpacing the average 3.7 percent annual increase in total US prescription drug expenditures.[8] This growth was fueled by several factors.

The number of contract pharmacies has exploded from their start in 2010 to over 30,000 in 2021.[9] This growth was predominantly fueled by national retail pharmacy chains. Walgreens was the first national chain to adopt a robust 340B strategy, amassing over 5,000 contract pharmacy locations by 2013.[10] CVS, Walmart and Rite Aid had fewer than 775 contract pharmacies each in that year; however, by 2020 they had 5,400, 2,900 and 1,470 contract pharmacies respectively, while Walgreens had grown to 7,900 unique locations.[11] Contract pharmacy locations can have relationships with multiple 340B covered entities, including covered entities that are not geographically close to the covered entity, so the number of total contract pharmacy and covered entity agreements is much higher than the 30,000 reported.

This lack of geographic proximity is one reason that while growth in the 340B program has outpaced overall pharmacy growth for all pharmacy distribution channels (e.g., retail, hospital, clinic and mail), growth in 340B prescriptions distributed via mail order has grown by more than five times in recent years.[12] Insurer consolidation has further contributed to this growth, as insurer-owned PBMs have dominated the PBM market, and these PBMs own specialty pharmacies that can serve as 340B contract pharmacies.[13]

An increasing number of 340B contract pharmacies alone would not result in the program’s growth, as these pharmacies only purchase drugs through the program when a 340B covered entity they are contracted with writes the prescription. The growth in the 340B program has been fueled by an increase in 340B covered entities as well.

As a result of the passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and the expansion of Medicaid in many states, the percentage of Americans with Medicaid coverage grew from 13.4 percent in 2008 to 19.8 percent in 2019.[14] Even before the ACA, Medicaid enrollment had been growing slightly. As a result, more hospitals qualify as 340B covered entities through the DSH criteria, which use as a key input the percentage of inpatient bed days provided to Medicaid patients as a percentage of all inpatient bed days. At the same time, the relative need for the 340B program may have decreased, as patients who were previously uninsured and the recipients of uncompensated care gained insurance coverage (largely through the Medicaid expansion).

Growth in the 340B program has been further fueled as hospital systems purchase physician practices, especially in those specialties with significant high-cost drug spend (hematology/oncology, ophthalmology and rheumatology). A 2018 study published in the New England Journal of Medicine found that 340B qualified hospitals had 230 percent more hematologist-oncologists, 900 percent more ophthalmologists and 33 percent more rheumatologists per hospital practicing in facilities owned by the 340B hospital than non-340B qualified facilities had.[15]

Another factor in the growth of the 340B program is the dramatic increases in brand drug list prices, which have greatly outpaced the net price of these same drugs. Net prices for brand-name drugs decreased by 2 percent to 3 percent per year between 2017 and 2020, but that was due to drug rebate amounts increasing at double-digit rates.[16]

There are several industry incentives for this type of pricing, one of which is due to the 340B program. In the earlier example, the 75 percent 340B discount achieved allowed the contract pharmacy and covered entity to share almost $3,750 in 340B margin. If the list price (WAC) doubled to $10,000 and the rebate percentage increased from 75 percent to 87.5 percent, the margin would increase 133 percent to $8,750 while the acquisition cost paid for the drug by the 340B covered entity would be unchanged.

If there were two therapeutically equivalent drugs, one with the $5,000 list price and 75 percent rebate, and another with the $10,000 list price and 87.5 percent rebate, a 340B covered entity could have a financial incentive to prescribe the drug with the higher list price. Pharmacy benefit managers may similarly have incentives to prefer these drugs on their formularies (due to serving as 340B contract pharmacies as well as other industry factors). These preferences increase revenue due to higher volume for the manufacturer that pursued the higher list/higher rebate pricing strategy compared to the lower list/lower rebate pricing strategy alternative.

Potential Problems

With drug purchases through the 340B program getting larger than all non-340B purchases for all of Medicaid (when measuring 340B purchases at their undiscounted amounts),[17] critics of the program are growing. While they may sharply disagree about the nature of the problems, everyone recognizes that there are difficulties.

From a policymaker perspective, the fact that most 340B discounts do not accrue any direct savings to the member is concerning. A patient who receives a drug purchased at a 340B discount likely sees no difference at the pharmacy counter than a patient receiving a drug purchased outside of the program. The program’s covered entities claim that retaining those discounts is needed to offset costs incurred from uninsured patients or those covered by government programs with insufficient reimbursement rates. True as those claims may be, the inability to draw a clear connection between the 340B program’s discounts and expanded access to needed medication for indigent patients is disturbing.

The 340B program may even facilitate a type of “reverse equity,” in which members taking high-cost medications pay higher cost-sharing amounts on drugs that at the same time offer significant 340B margins to PBMs and/or health plans, which can then be used to reduce premiums for all members (most of whom are relatively healthy compared to the member whose higher cost-sharing may benefit them).

Physician practices worry about the role 340B plays in provider consolidation and changing sites of care. Hospitals that are 340B covered entities can have a financial incentive to acquire physician practices comprising specialties that prescribe many high-cost drugs (e.g., oncologists, rheumatologists) because the acquisition can be used to steer members to receive their medications at the facility. This increases costs for members and health plans, as facility infusion services may be significantly more expensive than office-based and/or home-based infusion.

Hospitals are concerned with the explosive growth of contract pharmacies and the diversion of 340B margins from facilities to these contract pharmacies. Many hospitals are expanding their pharmacies to dispense specialty drugs and accommodate all of a patient’s needs without the involvement of the contract pharmacy.

Pharmaceutical manufacturers are concerned about paying rebates on drugs purchased through the 340B program, which in some situations could result in paying more in discounts and rebates than the net cost of the drug. While “duplicate discounts” are statutorily prohibited in Medicaid, enforcement of these provisions is the responsibility of manufacturers for commercial and Medicare health plans, and even within Medicaid the administrative complexity of the 340B program means that duplicate discounts sometimes occur. Manufacturers require pharmacies, health plans and PBMs to provide claims data so they can be audited for rebate eligibility, threatening not to provide drugs through the 340B program if this requirement is not met.

Manufacturers have also begun refusing to allow contract pharmacies to purchase drugs through the 340B program,[18] sometimes as a blanket rule, but other times requiring covered entities to work with a discrete list of approved contracted entities. These requirements are an effort to ensure that 340B discounts are retained by covered entities and not used as profit centers for national pharmacy chains or PBM-owned specialty pharmacies; however, many lawsuits have been filed to challenge these manufacturer decisions, alleging that the manufacturers are arbitrarily and unlawfully restricting the 340B program to protect their bottom lines.[19]

Potential Solutions

The Supreme Court has said in no uncertain terms that if Congress thinks there are problems with the 340B program, then Congress will need to fix those problems. Thus, robust policy discussions are taking place to ensure that the 340B program remains healthy and able to deliver on the noble intentions to which it owes its formation.

One proposed solution is to refine who qualifies to receive a 340B purchased drug. Currently, any patient who visits a facility that serves a particular proportion of Medicaid-covered patients (i.e., a facility determined to be a DSH) is considered a 340B patient, including patients who may be very much outside the program’s initial vision of indigent and medically needy populations. Because disproportionate share hospitals represent the majority of 340B spending, having 340B eligibility determined at the patient level rather than the facility level is one potential solution. However, these facilities may assert that the margins retained on 340B drug purchases from insured members are used to offset unreimbursed costs from uninsured or underinsured members.

Many are calling for increased transparency and accountability as a baseline reform. Most 340B covered entities do not currently have any obligation to report how they use 340B program funds, so it is impossible to evaluate whether the program is producing the types of benefits one would hope.

Restriction of contract pharmacies and their financial terms are other proposed reforms. The ability to have unlimited relationships has resulted in the nation’s largest PBMs and retail pharmacy chains dominating the 340B program. Limiting the number of contract pharmacies an entity may have could potentially slow the growth of 340B. Further, contract pharmacies’ financial arrangements with covered entities are secret (what we know comes from a report by the Office of the Inspector General). Requiring financial disclosure of terms or placing limits on the amount contract pharmacies charge covered entities for dispensing medications on their behalf could moderate profit growth. Slimming down the expansiveness of these contract relationships could still preserve a member’s ability to access medication while also somewhat tempering the extent of activity of PBMs and chain pharmacies. Another reform proposal is limiting the number of contract pharmacies with which a 340B covered entity can enter into an arrangement.

A final reform idea is to require that 340B discounts be transferred to the member (mirroring proposals for pharmacy rebates to be extended to members at the pharmacy counter). While this would more directly ensure that members receive the financial benefits of the 340B program, covered entities may argue that it is precisely those members who can pay full price who are needed to reimburse the hospital for members who cannot pay.

Conclusion

Like so many nooks and crannies of the complex US healthcare system, diverse, complicated and sometimes perverse incentives may impact many interconnected parties in distinct ways. While finger-pointing is a therapeutic activity to relieve well-intentioned frustration, a final assessment may conclude that the 340B program is, in a sense, working as intended—covered entities, contract pharmacies, payers and manufacturers are all pursuing the incentives presented to them. Meaningful 340B reform will better align these incentives to optimize patient care by preserving access to medications and the financial stability of care providers.

Statements of fact and opinions expressed herein are those of the individual authors and are not necessarily those of the Society of Actuaries, the editors, or the respective authors’ employers.

Tony Pistilli, FSA, MAAA, CERA, CPC, is a consulting actuary at Axene Health Partners, LLC. Tony can be reached at pistilli.tony@axenehp.com.

Endnotes

[1] American Hospital Association, 596 U.S. ___ (2022), https://kslawemail.com/128/9254/uploads/american-hospital-assn.-v.-becerra.pdf (accessed Feb. 15, 2023).

[2] US Department of Health & Human Services. Sec. 340B of the Public Health Service Act (42 U.S.C. 256b). eCFR, Jan. 5, 2017, https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-42/chapter-I/subchapter-A/part-10 (accessed Feb. 15, 2023).

[3] US Government Accountability Office. Drug Pricing: Manufacturer Discounts in the 340B Program Offer Benefits, but Federal Oversight Needs Improvement (GAO-11-836), Sept. 2011, https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-11-836.pdf (accessed Feb. 15, 2023).

[4] Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Learning Network Fact Sheet: Medicare Disproportionate Share Hospital. CMS, March 2021, https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/Downloads/Disproportionate_Share_Hospital.pdf (accessed Feb. 15, 2023).

[5] 340B Health. 340B DSH Hospitals Provide Three-Quarters of Medicaid Hospital Services. 340BInformed, July 16, 2020, https://340binformed.org/2020/07/340b-dsh-hospitals-provide-three-quarters-of-medicaid-hospital-services/ (accessed Feb. 15, 2023).

[6] Health Resources and Services Administration. 2010. Notice Regarding 340B Pricing Program—Contract Pharmacy Services. Federal Register 75, no. 43: 10272. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2010-03-05/pdf/2010-4755.pdf (accessed Feb. 15, 2023).

[7] Mulligan, Karen. The 340B Drug Pricing Program: Background, Ongoing Challenges and Recent Developments. USC Schaeffer, Oct. 14, 2021, https://healthpolicy.usc.edu/research/the-340b-drug-pricing-program-background-ongoing-challenges-and-recent-developments/ (accessed Feb. 15, 2023); Fein, Adam J. The 340B Program Soared to $38 Billion in 2020—Up 27% vs. 2019. Drug Channels, June 16, 2021, https://www.drugchannels.net/2021/06/exclusive-340b-program-soared-to-38.html (accessed Feb. 15, 2023).

[8] Kamal, Rabah, Cynthia Cox and Daniel McDermott. What Are the Recent and Forecasted Trends in Prescription Drug Spending? Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker, Feb. 20, 2019, https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/recent-forecasted-trends-prescription-drug-spending (accessed Feb. 15, 2023).

[9] Fein, Adam J. 340B Continues Its Unbridled Takeover of Pharmacies and PBMs. Drug Channels, June 15, 2021, https://www.drugchannels.net/2021/06/exclusive-340b-continues-its-unbridled.html (accessed Feb. 15, 2023).

[10] Fein, Adam J. The Booming 340B Contract Pharmacy Profits of Walgreens, CVS, Rite Aid and Walmart. Drug Channels, July 11, 2017, https://www.drugchannels.net/2017/07/the-booming-340b-contract-pharmacy.html (accessed Feb. 15, 2023).

[11] Fein, Adam J. Walgreens and CVS Top the 28,000 Pharmacies Profiting from the 340B Program. Will the Unregulated Party End? Drug Channels, July 14, 2020, https://www.drugchannels.net/2020/07/walgreens-and-cvs-top-28000-pharmacies.html (accessed Feb. 15, 2023).

[12] Martin, Rory, and Shiraz Hasan. Growth of the 340B Program Accelerates in 2020. IQVIA, Mar. 31, 2021, https://www.iqvia.com/locations/united-states/blogs/2021/03/growth-of-the-340b-program-accelerates-in-2020 (accessed Feb. 15, 2023).

[13] Fein, Adam J. Mapping the Vertical Integration of Insurers, PBMs, Specialty Pharmacies and Providers: A 2022 Update. Drug Channels, Oct. 13, 2022, https://www.drugchannels.net/2022/10/mapping-vertical-integration-of.html (accessed Feb. 15, 2023).

[14] Kaiser Family Foundation. Health Insurance Coverage of the Total Population. KFF, 2021, https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/total-population/ (accessed Feb. 15, 2023).

[15] Desai, Sunita, and J. Michael McWilliams. 2018. Consequences of the 340B Drug Pricing Program. New England Journal of Medicine 378: 539–48. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMsa1706475?query=recirc_curatedRelated_article& (accessed Feb. 15, 2023).

[16] Fein, Adam J. Key Insights on Drug Prices and Manufacturer Rebates from the New 2015 IMS Report. Drug Channels, Apr. 19, 2016, https://www.drugchannels.net/2016/04/key-insights-on-drug-prices-and.html (accessed Feb. 15, 2023); Fein, Adam J. Gross-to-Net Bubble Update: Net Prices Drop (Again) at Six Top Drugmakers. Drug Channels, Apr. 14, 2021, https://www.drugchannels.net/2021/04/gross-to-net-bubble-update-net-prices.html (accessed Feb. 15, 2023).

[17] Longo, Nicole. 340B Program Remains Second Largest Federal Drug Program, yet Little Solid Evidence of Benefits to Patient. PhRMA, June 30, 2022, https://catalyst.phrma.org/340b-program-remains-second-largest-federal-drug-program-yet-little-solid-evidence-of-benefits-to-patient (accessed Feb. 15, 2023).

[18] 340B Health. Protect Patients: Stop 340B Cuts! 340BInformed, n.d., https://www.340bhealth.org/newsroom/stop340bcuts/ (accessed Feb. 15, 2023).

[19] Ryan White Clinics for 340B Access. Update on 340B Contract Pharmacy Litigation Decisions Issued in Four Manufacturer Lawsuits. RWC-340B, n.d., https://rwc340b.org/update-on-340b-contract-pharmacy-litigation-decisions-issued-in-four-manufacturer-lawsuits/ (accessed Feb. 15, 2023).