A Mental Health State of the Union

By Traci Hughes

Health Watch, May 2023

During my middle school years is when I first started going to therapy for help dealing with anxiety. My parents, not being mental health professionals, lacked the knowledge of tools and methods that could help me through my struggle to cope. One of the best things they have ever done for me is to admit that they needed the help of someone else in order to help me most effectively.

The second time in my life I started going to therapy, as a young adult, I was in a great place in my life overall but just had certain challenges I couldn’t seem to push past or fully process on my own or with the help of those around me. I was skeptical about whether therapy was a “viable” course for me. My only regret is that I didn’t start earlier—or that I didn’t just continue the therapy I had as a child at a maintenance level. It helps me significantly, has been a defining decision in my life’s path and is the reason I am able to maintain a mentally healthy lifestyle.

As I am sure any reader will have guessed, I am an actuary, not a mental health professional. However, I am a person with my own mental health experience. As such, I will write about what I’ve learned via my own experience as well as what I’ve learned via research. What I intend to capture in this article is the state of mental health and health care in the United States as it stands now and where it’s heading as we move forward.

Defining Mental Health and Mental Illness

While similar in nature, there are various definitions of “mental health.” It can be defined as our emotional, psychological, and social state of being, compared to physical health, which can be defined as the level of the body and organ’s proper functioning. For the purposes of this article, we will use these definitions.

With this perspective, referring to mental health is not the same as referring to someone’s good mental health nor the same as saying someone is mentally healthy. Physical and mental health are usually not simply “good” or “bad.” For example, someone could have an aspect of physical health that is poor but still be a generally physically healthy person overall. In other words, there’s a spectrum from 0 percent healthy and 100 percent healthy, and the buckets for using descriptors such as “good” or “bad” are subjective.

Mental illness, on the other hand, can be defined as a diagnosable condition that affects a person’s thinking, feeling, mood or behavior. I find this to be a little different than how we, as a society, define and refer to physical illness, mainly due to what is considered a diagnosable condition when it comes to mental health. Whether we have a simple common cold or are hospitalized with pneumonia, we are experiencing a physical illness; we are “sick,” and it is “diagnosable.” However, the version of a simple common cold when it comes to mental health is labeled “stress,” “a funk,” or something similar (i.e., not a “diagnosable” condition). These labels are not referred to as mental illnesses unless or until they intensify enough to be diagnosed as “disorders.” For the purposes of this article, I will refer to the more general, emotional labels as mental health challenges.

The Current State of Mental Health

It is difficult to answer the question “How mentally healthy is America?” because the data available to assess mental health challenges (i.e., mental health indicators other than mental illness incidence and prevalence) are self-assessed. Not only do the self-assessments have subjective options, but it can also be very difficult to properly assess one’s own mental health, even for mental health professionals.

Regarding mental illness, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), approximately 20 percent of Americans experience mental illness in any given year, and more than 50 percent will be diagnosed with a mental illness at some point in their lives[1]. Just like a physical illness, mental illnesses and mental health challenges can be short term (acute) or long term (chronic) in nature. Regarding mental health challenges and other mental health status indicators, Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) data shows that in any given month, approximately 40 percent of adults report having at least one poor mental health day.[2] On average, adults report having about four poor mental health days per month.[3]

A 2022 KFF survey found that 22 percent of adults report their mental health as “less than good.”[4] It is important to shed light on the fact that among adults older than 65 that percentage was 9 percent and increased steadily with each younger age bracket, reaching 34 percent at ages 18–29. This is likely some combination of a true trend of declining mental health in younger people and an older generation’s underreporting of poor mental health due to their relatively heightened belief in its stigma[5] and lower level of mental health education.

Regarding the declining mental health in younger people, several factors are believed to be contributing to this trend:

- Social media. While social media doesn’t decrease mental health for all individuals, a 2022 study by Cambridge University shows that social media use is correlated to lower life satisfaction at all ages on average. Additionally, the decrease is most pronounced for individuals aged 11 to 14.[6] However, a 2020 meta-analysis noted that while social medica can affect anxiety and depression levels, correlation has not necessarily proved direct causation. It states that further investigation is required to help examine why social media has a negative impact on some peoples’ mental health while having no impact or a positive impact on that of others.[7]

- Gun violence. A study published in 2021 in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) found a strong correlation between concerns about school violence or shootings and generalized anxiety disorder.[8] This concern is increasing among children and adolescents.[[9]]

- Other factors. While less studied, other suspected contributors are increasing concerns around climate change/global warming[10] and growing income and wealth gaps leading to a larger portion of stressors such as hunger and lack of other basic needs for low-income families.[11]

Whatever the cause, it is objectively a very real trend and it’s making a big impact. Suicide rates among adolescents have almost doubled from 3.9 to 6.3 per 100,000 from 2010 to 2020.[12] Over the same time frame, self-harm rates among adolescents have grown at a similar rate from 99 to 177 per 100,000.[13] These statistics should not be misconstrued to be of mental illness itself; these are of symptoms from often untreated mental health challenges and illnesses.[14]

Underemphasis on Prevention

Despite decreasing stigma around mental illness in the US, mental health care is still overwhelmingly reactive rather than preventive. Physical health care may not be much less reactive in the US health care system, but it is certainly more commonplace to get an annual physical, vaccinations, cancer screenings and so on than it is to have, say, an annual or quarterly visit with a therapist, counselor or other mental or behavioral health provider.

There is a general opinion that we don’t need therapists unless our problems get “big enough.” However, “big enough” is very subjective and often hard to recognize in ourselves—most of the time we are sure that we are “strong enough” or “not really going through that much.” In my own personal journey, I have been in that place. But in reality, many people with poor mental health are just feeling stuck in the same things we all struggle with at times: relationships, self-doubt, work/life stress, transitional life stages, anxiety and so on. We often think these are the things that are not “big enough” for therapy, but they are the exact challenges that, when left untreated or to unhealthy coping mechanisms, lead to worsening and eventually severe mental illness in some cases.

An example is the experience of microtraumas. We usually think of trauma as a big, life-altering event that leaves a lasting impact, and that is one type of trauma. But microtrauma is a subtler form that happens over time. Microtraumas can be defined as seemingly insignificant experiences that are emotionally hurtful to oneself or another. Because they seem so minor, they can easily be ignored, denied or otherwise swept under the rug. These subtly hurtful experiences can accumulate over time, and they can eventually cause a lasting impact just like singular traumatic events, inflicting psychological harm on one’s self-worth, security and well-being.[15]

Of course, not every mental health challenge requires a therapist any more than every physical malady requires a physician. If I have a sinus headache, I use over-the-counter medications or home-care methods rather than seeing a doctor. However, in my own journey, I have decided that it is best to have at least four to six visits with my therapist annually. The purpose being, at a minimum, to stop and evaluate where my mental health stands periodically with the help of a professional. With these periodic visits I am able be reminded of or learn about more tools or methods I can use in my daily life to help with anything I might be struggling with mentally or emotionally. I see this as preventive mental health care. Preventively, for my physical health, I see my dentist twice a year, gynecologist once a year and primary physician once a year. Why shouldn’t I have at least the same number of preventive care visits for my mental health?

However, I am very fortunate that I have access to this kind of care without financial or other barriers being an issue.

Barriers to Mental Health Care

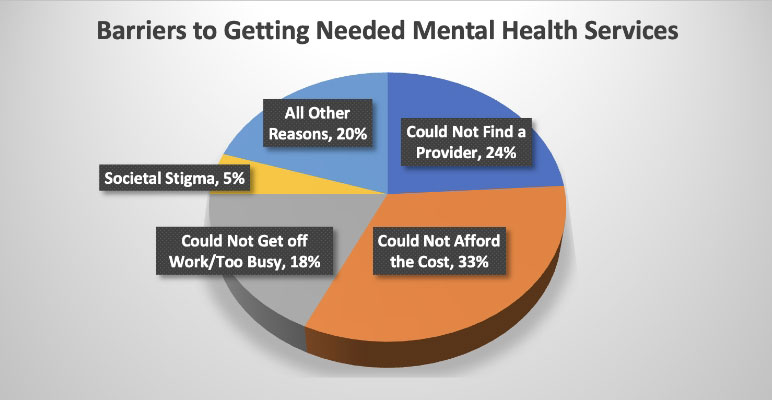

Figure 1 shows the top five barriers for those who noticed a need for mental health services but did not ultimately receive those services per a 2021 KFF study.[16]

Figure 1

Barriers to Getting Needed Mental Health Services

There is a current shortage of mental health providers. In conjunction with the growing demand for mental health services in recent years, it can be very difficult to find a provider for the care needed. Exacerbating this issue is that approximately 90 percent of primary care providers accept insurance, whereas only approximately 55 percent of mental health care providers accept insurance. When county-level National Provider Identifier (NPI) data is adjusted for the difference in in-network coverage, only 66 percent of counties have an equal amount or more in-network mental health care providers compared to in-network primary care providers (PCPs) per capita.[17]

The lack of in-network mental health providers is due, in part, to an overall supply shortage and also to low network reimbursement rates negotiated by insurers. On average, in-network mental health providers are reimbursed at 20 percent less than in-network primary care and other specialist-type providers. Under the circumstances of low network reimbursement rates, low supply and high demand, mental health providers can receive an average of 80 percent more in reimbursement per unit under a private-pay model compared to an in-network insurance model.[18]

This leaves significant groups of insured members either (1) unable to find an in-network mental health provider; (2) unable to find any mental health provider, regardless of whether they are in-network; (3) able to find an out-of-network mental health provider but unable to afford private-pay prices; or even (4) able to find an in-network mental health provider and still unable to afford the out-of-pocket cost share. The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) has helped to reduce mental health service cost share, but it is still about $65 per outpatient service unit on average.[19] For low-income families this may not be affordable, especially if more than one visit is needed, which is often the case. It should be noted that low-income families and individuals are increasingly vulnerable to stressors such as accessibility to and affordability of food, housing and other essential needs that, in general, significantly contribute to poor mental health.

Looking to the Future

In the Biden Administration’s first State of the Union address (March 2022), a national mental health strategy was announced.[20] The strategy includes:

- Launching the 9-8-8 mental health crisis response line. A companion to the 9-1-1 emergency response line, this is a separate hotline available to those experiencing a mental health crisis. It was launched in July 2022. This item is primarily aimed at addressing the increases in suicide rates.

- Strengthening the mental health parity and emphasizing preventive mental health benefits. The address states that the fiscal year (FY) 2023 budget would propose that all health plans cover robust behavioral health services with an adequate network of providers, including at least three behavior health visits each year covered with no insured cost-sharing. Aside from this statement, I was not able to find any further information on the status of the proposal as of early 2023. However, if implemented, it could be a huge feat in shifting to a more preventive model of mental health care. It could address current reimbursement levels for mental health providers (via network adequacy requirements), cost barriers and the underemphasis on preventive care all at once.

- Expanding access to tele- and virtual mental health care options. According to FairHealth’s Monthly Telehealth Regional Tracker,[21] psychotherapy has consistently held two or three of the top five procedure codes of all tele-provided services from March 2020 through the most recently reported month, November 2022. It held none of the top five codes prior to Mach 2020, the igniting factor being COVID-19. To maintain continuity of access, the Administration stated that it planned to work with Congress to ensure coverage of tele-behavioral health across health plans and support appropriate delivery of telemedicine across state lines. At the same time, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) is tasked with creating a learning collaborative with state insurance departments to identify and address state-based barriers, like telehealth limitations, to behavioral health access. It should be noted that many insurers currently require providers to have a physical office address even if they provide 100 percent virtual services. In some cases, this causes providers to choose not to participate in the insurer’s network. In these cases, providers do not want the extra overhead cost of a physical office when they can still get a healthy patient load under a private-pay model while working from home. The Administration’s initiatives to address access to virtual mental health care options are primarily aimed at addressing access inequities. They could also address the “work/busy/lack of time” barrier by removing the commute to access services, especially in rural areas where it may otherwise require a 60+ minute commute each way.

- Investment in proven programs that bring providers into behavioral and mental health. This involves a FY 2023 investment of $700 million in programs that provide training, access to scholarships and loan repayment to mental health and substance use disorder clinicians committed to practicing in rural and other underserved communities. This item is aimed at addressing both the provider shortage and access inequities.

- Expanding the availability of Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics (CCBHCs). CCBHCs are clinics that provide a comprehensive array of behavioral and mental health services, are available 24/7 and are required to serve anyone who requests care, regardless of their ability to pay or place of residence. The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) invested millions of dollars to expand CCBHCs. The FY 2023 budget will include further investment in CCBHCs by allocating state funds for communities that need these services the most. This item is primarily aimed at cost barriers and access inequities.[22]

These items are only a part of the overall national mental health strategy that was announced. Let’s all hope that there is ultimate follow-through in implementing the comprehensive strategy and that it makes a significant impact in improving the current state of mental health care in US. While lawmakers and insurers can help clear barriers, ultimately, each person must make a choice to care for their own mental and physical well-being. An annual physical may be covered at no cost, but the patient still must make the choice to set up the appointment and show up at the doctor’s office. Society can make it easy to forget about or dismiss mental health needs, but please do not buy in to this status quo. Each person has the power to stop ignoring and start acknowledging their mental health needs. My challenge to you is to reflect on one thing you can do, either preventively or reactively, to attend to your mental health. “Rising tides lift all boats,” and we will all benefit.

Statements of fact and opinions expressed herein are those of the individual authors and are not necessarily those of the Society of Actuaries, the editors, or the respective authors’ employers.

Traci Hughes, FSA, MAAA, is a vice president and senior consulting actuary at Lewis & Ellis, Inc. Traci can be reached at thughes@lewisellis.com.