Property and Casualty JRMS Survey

By Frank Reynolds

Risk Management, April 2021

The Council of the JRMS considered the problems that would arise in trying to calibrate ERM models for the pandemic. It was felt that providing comparative figures for the industry would provide useful guidance for practitioners in justifying and making changes in these models. Unfortunately, the pandemic and U.S. anti-trust laws slowed the process more than anticipated so that the results could not be available before year end. In the hope that they still may be of use, this report gives a summary of the data reported.

Although the results of the survey were very disappointing in terms of number of replies, some insights may still be inferred from the limited responses. For most questions, the most common reply was “unknown,” indicating the expected uncertainties brought by the pandemic.

Seventy-three percent of the results came from the US and 18 percent from Canada. The rest were from Asia or other.

By size, most (16) were medium, four were small (under 500 million of premium) and two were large (over 50 billion of premium).

Three of 10 respondents reported an increase in productivity from working at home, one a decrease and the other no change. Of eight respondents, three expect a future increase in working from home, five were maybe and only one was no.

Performance

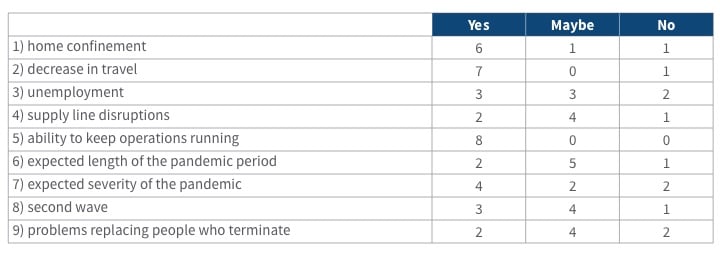

The following table shows how well the models were judged to perform (eight respondents)

The models did best in forecasting the ability to keep operations running, the decrease in travel and the home confinement that occurred. Weakness showed in forecasting supply line disruptions, the expected length of the pandemic period and the ability to replace people who terminated.

No one reported a liquidity incident. Of six respondents, two felt their scenarios inadequate, three reasonable, and one good. Two respondents felt their liquid reserves were adequate, and four that they were sufficient.

Stress testing—of 10 respondents, two have done extensive stress testing to test resiliency to COVID-19, seven moderate testing, and one some testing,

Splitting the results by epidemic versus results of the epidemic indicates that while the models did a reasonable job of anticipating the epidemic’s severity and effect on liquidity, there were weaknesses in predicting the second wave and the duration of the pandemic. By and large the results were not well predicted—supply line disruptions, the ability to replace people who terminated, and the extent of unemployment. Since the results lead to estimates of financial effect and are the purpose of building the models, it would appear that a lot of revision of thinking is in order.

Experience Changes by Line of Business

Note: in many cells the number of respondents was about five or less, so the results are not actuarially significant.

1) Automobile—minor and major accidents declined by about 5 percent, but the cost per accident increased about 10 percent. Most offered rebates—typically of 15 percent. The rebates were given to all, typically, but one insurer used customer statements. Non-renewals did not change.

2) Theft and vandalism—both minor and major claim rates remained the same. Cost per claim remained stable. One respondent reported a decrease in non-renewal while five reported no change.

3) Workers compensation—three respondents reported no change, three decreases averaging 15 percent, and one an increase of 25 percent. Two of seven respondents reported cost per claim rose 10 percent. Two of the respondents felt that scenarios did not address the problems, two that the scenarios were inadequate, and two that the scenarios did reasonably. One company expected to make changes in wording and one to make changes in pricing next year.

4) People not in the medical professions and long-term care—four respondents reported covering claims the same and three not.

5) Business interruption claims—one respondent reported no change while six reported changes—three of 5 percent to 10 percent and one of over 30 percent. The effect on cost per claim was unknown. Three respondents felt their scenarios were inadequate, four reasonable and two the situation was well covered. Four respondents intend to change policy wording and two both wording and pricing.

6) Fire claims—no changes in claims were reported for minor and major fires, although one respondent reported a 15 percent increase in cost per claim. Non-renewals remained constant.

7) Liquidity—no one reported a liquidity incident. Of six respondents, two felt their scenarios inadequate, three reasonable, and one good. Two respondents felt their liquid reserves were adequate, and four that they were sufficient.

8) Stress testing—of 10 respondents, two have done extensive stress testing to test resiliency to COVID-19, seven moderate testing, and one some testing.

I would like to thank Florian Richards for his excellent work in taking my rough draft to the polished survey.

Statements of fact and opinions expressed herein are those of the individual authors and are not necessarily those of the Society of Actuaries, the editors, or the respective authors’ employers.

Frank Reynolds, FSA, MAAA, FCIA, is chair of the Joint Risk Management Section, a retired university Professor and president of Reynolds, Thorvardson, Ltd. He can be contacted at fgreynol@gmail.com.