Introduction to Credit Risk Exposure of Life Insurers

By Jing Fritz

Risk Management, September 2022

In my debut article published in the February newsletter earlier this year, I briefly mentioned insurers take credit risks on investments to support the commitments made to their policyholders. A few sentences are far from doing justice to the complexity of credit risks faced by insurers. I’ve taken the feedback received from my debut article to heart and plan to share my thoughts on this topic in several articles. In the next few articles of this series, I am going to give a high-level overview of credit risks for life insurers. This article is dedicated to the non-statutory accounting treatment of common credit risk exposures of life insurers but does not cover all aspects of non-statutory accounting standards. It introduces the concept of and the valuation of credit risks, concerning life insurers, both of which will be expanded further in later articles.

The Tales of Two Credit Losses

In response to the 2008 financial crisis, International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) published International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) 9, concluding an overhaul of accounting standards for financial instruments. The concern that the IFRS 9 tries to address is that the accounting measurement under the prior accounting requirements didn’t reflect risk exposure properly until it was too late. Don’t get me wrong, inadequate risk management is still the root cause for the crisis, but the point is that deficiency in accounting measurement and reporting or the lack of transparency into the risk management didn’t help.

Even though Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) and IASB have been working together since 2002 to improve and converge U.S. GAAP (generally accepted accounting principles) and IFRS, FASB didn’t incorporate IFRS 9 into the U.S. financial reporting system, but instead published its own accounting changes. IFRS 9 covers changes in classification and measurement, impairment and hedging accounting. FASB made changes to these areas as well, but they did it in stages with different standards. What both boards agreed upon, however, is that the impairment or credit loss accounting needs to change. The unfavorable event driven approach on impairment gave way to Expected Credit Losses (ECL) under IFRS 9 and to Current Expected Credit Losses (CECL)—ECL’s cousin in the US. FASB also tweaked impairment accounting for the assets classified as available for sale (AFS) but they are excluded from the scope of CECL.

Under the old regime, the impairment was the incurred credit losses, in determining which only past events and current conditions are used. Credit losses were booked after a credit event had taken place, thus the name “incurred.” ECL and CECL require the incorporation of forward-looking information in addition to the past/current info in the calculation of impairment. There will be an allowance for credit losses since initial recognition regardless of the creditworthiness of the investment asset. The allowance can be perceived as the reserve or capital for credit risks. In practice, the allowance could be zero if there are no expected default losses for the instrument, US Treasury bonds, US Agency MBS, just to name a few.

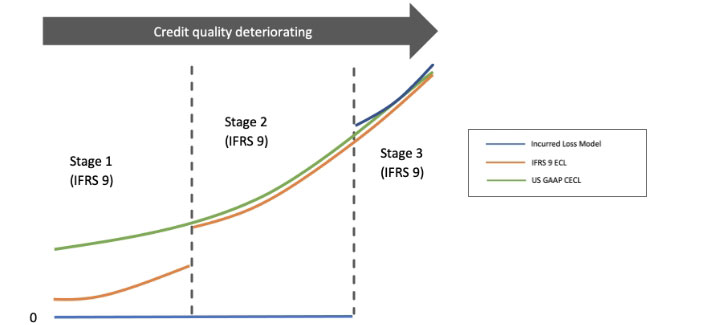

ECL under IFRS 9 is typically calculated as a probability weighted estimate of the present value of cash shortfalls over the expected life of the financial instrument. It Is an unbiased best estimate with all cash shortfalls taking into consideration the collaterals or other credit enhancement. Four typical parameters underlying its calculation are: Probability of default (PD), loss given default (LGD, i.e., 1-Recovery Rate), exposure at default (EAD) and discounting factor (DF). Prepayments, usage given default (UGD) and other parameters can also play a role in the calculations. In the general approach the loss allowance for a financial instrument is 12-month ECL regardless of credit risk at the reporting date, unless there has been a significant increase in credit risk since initial recognition: The PD is only considered for the next 12 months while the cash shortfalls are predicted over the full lifetime; as the creditworthiness deteriorates significantly, the loss allowance is increased to full lifetime ECL in Stage 2, which should always precede stage 3 (credit impairment). Even without change of stages, any credit condition changes should be flowing into the credit loss allowance via updates in some of the underlying parameters. Exhibit 1 has an illustrative comparison between ECL, CECL, and incurred loss model.

CECL is similar to ECL except FASBs doesn’t have so-called staging as IFRS 9, which requires that only 12-month ECL is calculated in stage 1 (in the general model). In other words, CECL requires a full lifetime ECL from Day 1. There are also other differences: IFRS 9 requires certain consideration of time value of money, multiple scenarios, etc., in measurement of ECL while US GAAP CECL doesn’t.

Under US GAAP, different from CECL, currently the impairment for AFS assets, while also recorded as an allowance (with a couple exceptions), is only needed for those whose fair value is less than the amortized cost. Once it is triggered, the credit losses are then measured as the excess of the amortized cost basis over the probability weighted estimate of the present value of cash flows expected to be collected. Only the fair value change related to credit is considered in the calculation of AFS impairment. The quantitative calculation behind the probability weighted best estimate is like CECL/ECL. Both can use discounted cash flow methods with parameters such as PD although one is calculating expected cash shortfalls directly in CECL and the other is calculating the expected collectible cash payments and then is used to back out the impairment.

Exhibit 1

Illustration of ECL, CECL, and Incurred Loss Model

The credit risk measured in the ECL/CECL/AFS impairment is only related to default risk: The losses in the event that the obligor defaults. The risk of credit rating migration is also reflected in ECL/CECL/AFS impairment. As shown in Exhibit 1, ECL/CECL would increase as the credit quality deteriorates; ECL jumps up to be close to CECL upon entering stage 2 as 12-month ECL is shifted to lifetime ECL. Credit spread movement alone, if it is not indicative of or rather caused by changes in credit risks, is not captured in ECL/CECL/AFS impairment. This distinction insulates the profit and losses (P&L) for financial assets under amortized cost (AC) and AFS or fair value through OCI (FVOCI; IFRS 9’s equivalent to AFS in FASB), from non-credit-risk-related noises in the credit spreads. That being said, how to identify and quantify these noises is easier said than done. We will come back to this in future articles. Also interest rate market movements are excluded as well. If time of value is considered, effective interest rate, assuming it is a fixed rate debt, could be used as the discount rate in the calculation.

Implication for Insurers

Accounting standards don’t differentiate between financial instruments held by an insurer versus a non-insurer. Take ECL for example, it is applicable to all financial assets as long as they are classified as AC or FVOCI (with recycling), regardless of who owns them. However, the implication of the standards is quite different for insurers from institutions in other industries.

As a financial institution, the majority of insurers’ assets are financial instruments. Among the financial instruments, a significantly large portion of the assets are lending agreements (in the world of IFRS 9, they will pass the sole payment of principal and interest test) and most fall under AC and FVOCI (for debt)/AFS and thus are subject to ECL/CECL or AFS impairment.

The obligors to the lending agreements are typically institutions including governments, instead of individuals. The financial statements for institutions are much harder to decipher than the financials of individuals like you and me (well, unless you are the likes of Warren Buffet). In addition to public corporate and government bonds, insurers also hold private corporate bonds and private corporate loans. Many, if not all, of these private debts or debt obligors are not rated by a rating agency.

- If a credit rating is available, it can be converted to the PD that could be used to calculate ECL/CECL/AFS impairment and potentially determine the staging in ECL. If the rating is not available, PD needs to be sourced elsewhere, which could entail extracting financial metrics by combing through financial statements of the obligators. Company’s internal rating or NAIC rating (for us in the US) could be the alternative to the rating agency’s rating. We will talk about internal rating and NAIC rating in subsequent articles.

- LGD or recovery rate is also harder to determine if the debt is not public. For a public bond, the price post default can provide a benchmark for LGD. There is no exit price we can look up for private debts although there are studies done by rating agencies and others. How much loss the company ends up recovering could depend on negotiation with the obligor and even litigation. Insurers might have to resort to having lawyers researching litigation cases to determine what can be recovered.

Insurers could have a sizable holding of structured credits, with stakes in the debt tranches. While insurers don’t directly lend to consumers, they indirectly tap into the consumer credit market by investing in structured assets with consumer loans as the underlying pool of assets, e.g., RMBS and ABS. Other structured credits such as CMBS and CLOs are also sources of asset yields for insurers. Empirically, defaults of MBSs as well as commercial mortgage loans (CRE; another asset type that is popular with insurers) have been studied extensively in attempts to understand the 2008 financial crisis; defaults of CLOs are relatively scarce even during the pandemic. The complexity of these structures makes the estimation of the underlying risk parameters very challenging. Sophisticated credit loss modeling is needed to support the ECL/AFS impairment calculation (typically these securities are classified as AFS in US GAAP), adding to a long list of reasons that insurers tend to leverage capacities of external vendors for the modeling of ECL/CECL/AFS impairment instead of going solo by themselves.

The contractual maturity of the insurer’s credit assets is long in order to back the long-dated liabilities. CECL, ECL, and AFS impairment all require projections for the full contractual term of each financial instrument (even the 12-month ECL needs an estimate of cash shortfalls for the entire remaining term). The overall credit risk is a combination of two different categories of risks: 1) the idiosyncratic risk, which could be chalked up to the characteristics of the debt and debt obligor (e.g., the debt type, the industry, etc.); 2) the systematic risk, which is driven by the overall economic condition. The underlying risk parameters are conditioned on the overall economy, for instance, typically defaults pick up during an economic downturn and drop during a boom. Predicting the economic outlook and more importantly the credit losses under each economic condition is very difficult. It is not unusual for economists to have different views on the economy. Weighting the credit losses under different economic scenarios (with a probability assigned to each scenario) is a good approach. However, the forecast tends to become more art than science after a couple of years, let alone 10+ years. The insurers are allowed to revert to historical information beyond reasonable and supportable forecast periods.

Credit quality wise, insurers lean toward investment grade credits. If we are to draw a line between Stage 1 and Stage 2 under IFRS 9 with the same line between investment grade and high yield, the CECL and ECL should be close for high yield assets, but not so much for investment grade as the former is lifetime and the latter 12-month.

Plot Twist

By now you learned that accounting treatment of financial assets are similar between CECL and ECL. There is a reason that I put emphasis on financial assets whenever I could. Earlier I mentioned that even though FASB and IASB took different paths of standards reform, they eventually came up with two credit losses based on the same principle. That is a convergence everyone is happy to see, and we could even tolerate the anomaly around AFS debt. The reality is that the convergence has its limit. Beyond financial assets, the accounting treatments of assets start to diverge. Insurance related assets, another category of common assets on an insurer’s balance sheet, is unfortunately one of those assets.

Insurance related assets (e.g., premium receivables, reinsurance recoverable, etc.) could be subject to CECL but should not be subject to ECL. IASB’s reform is ambitious and painstaking. It designated IFRS 9 to financial instruments and IFRS 17 to insurance contracts including reinsurance (I might be biased but the separation makes sense to me). As a result, any balances related to (re)insurance will be governed by IFRS 17. FASB published CECL and LDTI, but the impact of the change is not as widespread as IASB, not even close. US GAAP still has segmentations.

Here we are going to use reinsurance recoverable as an example to illustrate the difference. Let’s start with the US GAAP. Reinsurance recoverable is within the scope of CECL. The general methods for CECL as described in early sections also apply to reinsurance recoverable. The obligor in this case is a reinsurer who and/or whose ability to fulfill the contractual obligation is typically rated. Now let’s turn to the IFRS world. In IFRS 17, the risk of reinsurer defaulting on their obligation to the ceding company is captured on the ceding company’s book via adding a non-performance risk component into the valuation of the reinsurance contract held. In the case that the reinsurance held turns out to be a liability to the ceding company, the non-performance risk is not added. The change of best estimate liability and risk adjustment due to the change in non-performance risk doesn’t change the contractual service margin so it will be recognized in P&L directly, which is similar to how change in CECL is recognized.

Here comes the last twist. One exception to the reinsurance recoverable within the scope of CECL is market risk benefit (MRB; newly introduced by LDTI) reinsurance recoverable. As MRB is valued under fair value, nonperformance risk (NPR) of the reinsurer, along with many other risks, has been baked in by design. Although there is not a separate allowance, changes in MRB reinsurance recoverable due to movement in non-performance risk will flow into P&L, which in the end is also how change in CECL is recognized.

Conclusion

The actual accounting standards are more nuanced than how I put it in this article. If you fell asleep halfway through this article, I won’t recommend you read the accounting standards yourself, unless a nap is overdue. For our next article, we will look at the solvency/regulatory treatments of a life insurer’s credit risk exposure. I compared the accounting standards and highlighted the main discrepancies in this article. I won’t be able to present the same kind of comparison as there are variations in the solvency regulations and it is not an overstatement that each jurisdiction has its own set of rules. Within the US, there are even minor variances among states. Let me think through how I should write it. I will see you next time.

Statements of fact and opinions expressed herein are those of the individual authors and are not necessarily those of the Society of Actuaries, the newsletter editors, or the respective authors’ employers.

Jing Fritz, FSA, MAAA, CFA, FRM, CERA, is a senior manager at PwC and a member of the Joint Risk Management Section Council. She can be reached at jing.fritz@pwc.com.