What is a Professional? Some Answers From a Japanese TV Show

By Mary Pat Campbell

The Stepping Stone, May 2021

As I write this, I am watching a Grand Sumo tournament, which occurs every other month. Sumo is my favorite sport—it’s easy to understand, you can champion multiple wrestlers, and each match is very quick. The primary way I watch sumo is through NHK World,[1] a free streaming English language TV service from the main Japanese TV network. Alas, it can’t all be sumo, as the tournaments are only for 15 days every-other-month, so I’ve noticed other shows in NHK’s line-up.

One show in particular, “The Professionals,”[2] caught my eye recently. The show usually plays weekly, on Saturday mornings, running commercial-free for 45 minutes. In each episode, one person is profiled—the “professional”—covering their area or work, intended to display what is consummate professionalism. While chefs are often profiled, what is very interesting is the wide variety of professions that are covered, and not necessarily ones many of us would consider as “professions.”

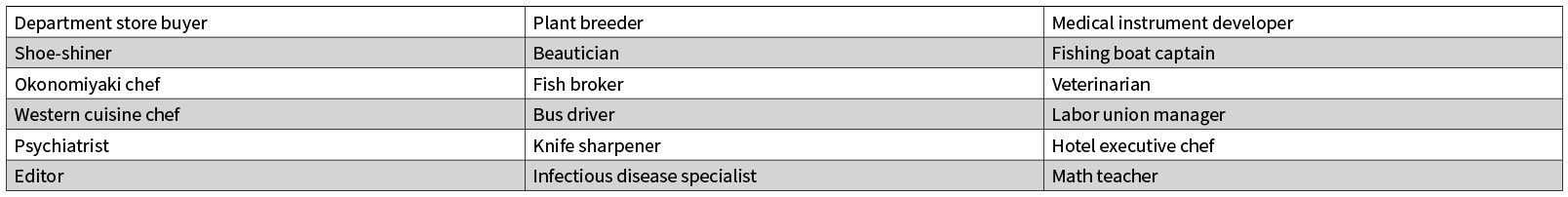

Table 1 is a sampling of the professionals’ jobs from over the past year:

Table 1

Examples of Professionals’ Jobs

It’s not really about the specific jobs—it’s about the people doing these jobs. In most cases, there are thousands of people in Japan who have that job. In a few cases, the person essentially created that job or business. Each person profiled has been pointed out to the producers as somebody who has shown exceptional results—exceptional food made, exceptional service given, exceptional results for their customers.

This program has run for over 15 years in Japan, with over 400 professionals profiled.

What are the lessons these profiles have shown?

Learning Through Experience, not Books

A common theme: The current level of perfection has been developed from many years of job experience. Usually, the people profiled on “The Professionals” were awful, or, at best, mediocre at the job when they first started.

For example, take the Okonomiyaki chef, Ichii Kaoru. Okonomiyaki is a type of street food in Hiroshima, a savory pancake where customers pick all sorts of additions to the pancake. In general, people aren’t expecting anything amazing from street food. And when Ichii Kaoru started out, there was nothing special about what he cooked, and he often mis-cooked the food. But over the years Ichii Kaoru developed his cooking technique to the point he was recognized by customers as having created something special. As part of the show, one customer requested that Ichii teach him how to make Okonomiyaki for his dying mother. Ichii told him he was very unlikely to get his results, but that he would train him as best as he could (in six weeks). Obviously, the novice was unable to replicate the results of the master who had been cooking this for decades, because so much of the information and skill came from the understanding built up from direct experience. While the novice fell short of Ichii’s results, he was still able to delight his mother with a special meal. More on Ichii’s experience later.

For those of us who have been in the business world for years, this is not a new lesson. We know that so much of what you need to know and understand to excel will have to be acquired by actually doing the job. It’s all very well to have formal schooling, but there are aspects that are very special to the job at hand that general schooling will not be able to teach you.

As many of us get older, we forget to tell those who come behind: We expect you to be ignorant when you start, and there is a great deal of implicit knowledge and skills you need to build up. Almost all of that development will come not through formal training, but from doing the job, failing, and learning from your failures.

It need not even be failures—it can be merely seeing that the service or product is mediocre and trying to figure out a better way to do it.

Omori Toru, a bus driver profiled on “The Professionals,” has an approach to driving his bus that has improved the experience of the riders. His approach is noticeably different from the techniques of other drivers, in how he takes turns on the very narrow, steep, and windy roads in his town of Hakone. Normal approaches lead to passengers swaying as they take turns sharply, and getting jolted at each bus stop as the driver brakes hard. Omori tries to minimize the jolting and swaying, as this can make the passengers feel ill. More on Omori’s technique in a moment.

On top of that, the people profiled have had their excellence recognized by other people … and that takes time. Often, what the people are trying to accomplish isn’t immediately appreciated or even recognized.

As a result, most of the people profiled in the show are middle-aged or older. Indeed, the oldest person profiled on “The Professionals” is “Granny Mochi,” Kuwata Misao, who was 93 when covered in 2019.

This is something that we should be telling the younger generations as well: Unlike school, in which we’re explicitly taught, tested, graded, and ranked, in the “real world,” the results can be murkier. It can take years of working towards excellence before anybody notices your results.

Attention to Detail Can Have Amplifying Effects

Let’s return to the bus driver, Omori Toru, and his technique to improve the passenger experience. In order to reduce the jolting of a hard stop at the bus stops, he flexes two of his toes in a particular way to ease into the stop. It’s a small finesse that leads to a happier outcome.

For Okonomiyake chef Ichii Kaoru, the detail he pays attention to is the change in sound of the sizzle as he cooks, as well as knowing the difference in temperature across his frying surface. For fish broker Hasegawa Hiroki, it’s a matter of paying attention to the activity of the fish he buys for his restauranteur clients, and the sheen of the skin. For “Granny Mochi” Kuwata Misao, it’s the dryness of the red beans she uses and the thickness of the bamboo leaves she chooses to wrap the mochi balls she makes.

Invariably, there is an attention to detail in the profiled professionals, but to be specific, it’s that these people have learned which details actually count. There are details in all sorts of things, but for the specific job at hand, some are much more important than others.

This is something I especially noticed, being a detail-oriented person myself. The point of paying attention to the details was to achieve something meaningful for a larger goal.

In the case of bus driver Omori, his over-riding goal is to provide a reliable and pleasant form of transportation in Hakone. This was the only profile I’ve seen that was actually filmed in 2020, after the COVID pandemic had spread into Japan. (There were other profiles filmed during the pandemic, but I hadn’t seen them.)

A large part of Omori’s bus routes cover areas mostly frequented by tourists, and in July 2020, there were almost no tourists in the Hakone area. Hakone had challenges pre-dating the pandemic, as there had been volcanic activity shutting down some tourist spots in 2019. Omori thought “past the bus stop,” getting out of his bus at major connection points, looking to see if there were any people who looked lost or confused (and therefore, were likely tourists). He would help them find their destination, and, of course, sometimes it would be his own bus that could take them there.

In all of the cases, it did not take superhuman skill or knowledge to achieve the results the various professionals achieved, but that you determine what the overarching goal is, and then paying close attention to what got you closer to that goal, and what did not.

Attitude is Important

This leads me to my final point: The people profiled on “The Professionals” all had an attitude that led to particular results. Their attitude was that their jobs had a particular value to other people, and that they were going to fulfill that job as best they knew how … and also to keep their eyes open to the possibilities of ways to do that job better.

Fish broker Hasegawa often saw a third of the fishing catch thrown out or turned into fish meal for feeding livestock. He thought a lot of value might have been thrown away, because the specific fish were seen as too difficult to process, or were bad-tasting given their treatment. Hasegawa considered this a big waste, and worked on seeing how he could get the best taste possible out of the specific fish. He became known as the “garbage man,” as he determined how to improve the fish—both by having tanks to revive the fish coming back from the catch, as well as determining fast, humane ways of killing the fish to keep the meat tasting better.

There are always two attitudes demonstrated in the profiles on “The Professionals”:

- The work is worth doing, and

- there is always something to learn to improve the work.

This leads the professionals to excel in what they do, no matter the field. The actual performance and results of the people profiled are outstanding, but what’s interesting is that they are within the reach of most people. None have any superpowers. They’re not particularly superintelligent nor psychic nor even lucky.

They realize that they can improve on what has been done before, via their own experience and observation. They learn from their failures and from trying out new things, and then adopting the behaviors they’ve learned leads to better results.

What is a Professional?

At the end of each episode of “The Professionals,” they ask the person profiled: “What is a professional?”

Here are some of the answers (translated into English):

Fish broker Hasegawa: “What’s important is how you live.”

Bus driver Omori: “It may not be a flashy job, but someone who puts in effort and pays attention to the detail.”

And finally, the oldest professional:

Granny Mochi: “The best way to live a life? Goodness, if only there were a textbook.”

Interviewer: “If you don’t know at 93, there’s no hope for me.”

Granny Mochi: “Ignorance can be bliss. … Accept that you can’t know, and good things will come.”

We have a limited life, and it’s okay that we don’t know. The work is worth doing, and we all can improve how we do the work.

Ganbatte![3]

Statements of fact and opinions expressed herein are those of the individual authors and are not necessarily those of the Society of Actuaries, the editors, or the respective authors’ employers.

Mary Pat Campbell, FSA, MAAA, PRM, is vice president, Insurance Research, at Conning in Hartford, Connecticut. She can be reached at marypat.campbell@gmail.com or https://www.linkedin.com/in/marypatcampbell/.