Are You an Empowering Leader?

By Russell Jay Hendel

The Stepping Stone, September 2023

It is well established that empowerment of staff is a critical leadership trait. But what are the metrics to recognize that you have achieved it? What steps enable this achievement? Which psychological attributes explain its efficacy?

This article proposes to answer these questions through a multi-disciplinary examination of empowerment in the context of three leadership domains:

- Manager-staff

- Instructor-student

- Doctor-patient

Each domain has its own language, methods and emphasis. By simultaneously reviewing all of them, a deeper understanding is achieved.

Manager-Staff Leadership

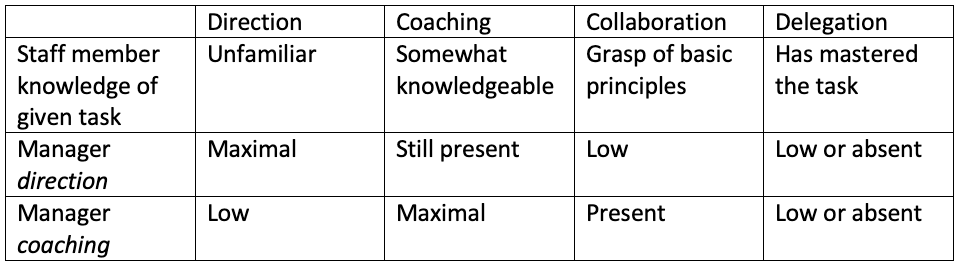

The Hershey-Blanchard situational leadership model[1] is summarized in Table 1, which provides necessary background on terminology, characteristics and methods.

A beginning staff member typically lacks knowledge and therefore needs manager direction on how to do required tasks. As the employee gains knowledge and experience, the manager must both direct and coach them to maintain the improvement. As the staff member gains further experience, the manager-staff relationship becomes one of collaboration, where the manager no longer needs to direct but instead supports the staff member’s independent thinking. Finally, upon achieving mastery, the manager can delegate tasks to the staff member with little oversight.

Table 1

The Four Stages of Situational Leadership

The Blanchard model refers to empowerment as delegation—the ability to assign a staff member a task without the need for constant review, support or oversight. This model views empowerment in terms of efficiency; the ability to delegate means that the same number of tasks are being accomplished but with less time spent. This is both because the staff member is efficient and can do the task quicker and because the manager no longer must spend time with the staff member to direct, coach or oversee.

At each stage, assessment is performative. That is, we measure what is being accomplished and what help is needed.

Instructor-Student Leadership

Although the models and leadership methods discussed in each section of this article do apply in any leadership context, different contexts may have different tendencies towards, and emphasis on, certain techniques. For example, the Blanchard model just discussed does not fully apply to the instructor-student domain, particularly for children in K–12. Typically, elementary school education does not empower students to collaborate equally in instruction, nor does it empower them to have the instruction delegated to them.

Thus, the instructor-student domain offers emphasis on leadership techniques alternative to those found in a business context. Additionally, literature on the instructor-student domain tends to focus more on the underlying psychology of the student rather than just performance.

We first review attribution theory which describes the psychological attitudes of students correlating with success.

Roughly speaking,[2] attribution theory studies how an individual explains successes and failures. In other words, it classifies the causes that a person attributes to success or failure. Four typical attributions of success and failure are luck, ability, effort, and instructor bias.

Attribution theory—independently rediscovered numerous times by varied authors—predicts that student attribution of success to internal controllable activities such as effort correlate highly with student success. Here, effort is something I personally do, it is internal and contrasts with instructor bias, which is external to me. Similarly, effort is something I can control in contrast to innate ability over which I have no control.

Although fairness of evaluation—that is, evaluation based on internal attributes the staff member controls—is relevant in any leadership context, it is more important in the instructor-student relationship, particularly with younger children who tend to be more accepting than adults.

The concept of effort naturally leads us to study the modern psychological concept of self-efficacy.[3,4] 19th century psychological theory held that unconscious drives and desires determined behavior. Contrastively, modern social cognitive theory holds that people are agents who can determine their own behavior. Central to social cognitive theory is the modern psychological concept of self-efficacy.

Self-efficacy is a specific form of confidence. It is the person’s belief that one can organize and integrate one’s current skills and knowledge to perform or succeed at a given task. Self-efficacy is important because it is the core agentic factor that determines people’s goal-directed behavior; that is, in a wide variety of learning situations, perceived self-efficacy highly correlates with success.

Achievement of self-efficacy is well understood and provides us with numerous specific steps and metrics helpful for understanding and implementing empowerment.

There are six drivers of self-efficacy,[5] the main driver being past performance successes, which neatly correlates with the concept of effort introduced in attribution theory. It is effort that leads to performance successes which in turn leads to personal satisfaction at achieving success, which motivates more effort and more successes. All this leads to the self-efficacy state of confidence.

Unlike the manager-staff relationship which identified empowerment with delegation, under the instructor-student relationship, empowerment refers to a feeling and perception, the perception of self-efficacy. The major metric for its achievement is past performance successes. The other five drivers associated with self-efficacy are[6]:

- Role Models: Self-efficacy is strengthened through observation and comparison with others who serve as role models. This includes observations of experts, observations of entire acts or specific act components, comparison with peers attempting to achieve the same goals, and even self-modeling, for example, videos of one’s entire successful past performances or important parts of them. Role models are best for self-efficacy when they fail, struggle, and then overcome that failure.

- Verbal persuasion: Self-efficacy is strengthened through verbal persuasion, evaluative feedback, self-talk, and verbal statements of expectations by others.

- Physiological reaction: Negative physiological reactions, such as headaches or fatigue associated with study or training, decrease self-efficacy; positive physiological reactions increase it.

- Emotional reactions: Negative emotional reactions, such as anxiety or discomfort associated with study or training, decrease self-efficacy; positive emotional reactions increase it.

- Imaginal experiences: Self-efficacy is improved through imagining oneself succeeding, practicing, or even imagining oneself confident.

Doctor-Patient Leadership

There are numerous articles and studies showing that knowledge and good doctor-patient rapport by themselves, while important, may not be sufficient to achieve critical medical preventatives. To illustrate, self-efficacy was found to be an important and critical predictor that is needed to achieve diabetes self-management,[7] medication adherence,[8] and appropriate mammography screening frequencies and behaviors.[9] We selected these three important preventative areas because they point to serious and widespread medical problems —medication non-adherence, lack of use of mammograms and poor diabetic self-management —with serious adverse medical consequences.

There is significant literature on barriers to self-efficacy and methods to improve it. One literature review[10] identifies three major barriers to patients for achieving self‐efficacy: poor health literacy, insufficient access and lack of support.

As noted, access to health care is a major contributor to patient self‐efficacy. Three critical aspects are:

- Gaining access to a health care system,

- Having access to the location of specialty services needed and

- Access to a trusted provider with whom one can easily communicate.

The most prominent barrier related to patients with chronic disease is lack of access due to location.

Patient support systems also play an important role in increasing self‐efficacy in patients. Support systems refer both to formal support systems such as health organization groups and informal support such as peer groups and family.

A review of the literature shows five prominent strategies that promote self‐efficacy: self‐management programs, telehealth, mobile applications, gaming, and social media.[11] Telehealth includes telephonic as well as more sophisticated methods of distant communication.

The literature on gaming to increase self-efficacy is exploratory and in its beginning stages but shows positive results. For example, one study exposed adolescents affected by chronic disease to a game for health called smart‐HD. This chronic disease intervention system provided participants with an avatar‐based health care professional, allowing them to practice and experience an interaction based on their specific disease process. The participants received real‐time feedback and educational resources to supplement the interaction.

The results were mixed, with some having positive outcomes and others having no change. Additionally, only a limited number of similar technologies addressed to adults have been tried. However, researchers note that the use of gaming in the self‐management of chronic disease could be a promising strategy.

These findings indicate that self‐efficacy for patients with chronic conditions can improve with new interventions. Enhancing traditional education and boosting self‐efficacy could increase treatment adherence and decrease cost.

Conclusion

This article has reviewed empowerment in a variety of leadership domains. We have seen that no matter how important knowledge and good leader-staff rapport are, failure or poor performance is more likely without perceived self-efficacy as achieved primarily through performance successes and good role models. We have also seen the importance of providing an environment where assessment is seen as objective, that is, dependent on internal behaviors of the staff member which they control.

The major steps needed to achieve empowerment are:

- The four stages of the Blanchard-Hershey leadership model coupled with

- An environment providing the staff member numerous performance opportunities and role-models that can serve as mentors, and

- An environment where assessment is seen as fair and objective.

The most important metrics for assessing continued achievement include measurement of staff self-efficacy, as described in endnotes [12, 13 and 14] at the end of this article, and measurement of staff attribution of successful assessment, as described in [15].

We hope these simple but concrete ideas can and will be adopted and implemented by leaders in their relationships with their teams leading to improved satisfaction and accomplishment.

Statements of fact and opinions expressed herein are those of the individual authors and are not necessarily those of the Society of Actuaries, the editors, or the respective authors’ employers.

Russell Jay Hendel, Ph.D., ASA, is the chair of the Education and Research Section council. He is adjunct faculty III at Towson University, where he assists with the Actuarial Science and Research Methods program. Russell can be reached at RHendel@Towson.edu.