Accounting for Assumed Reinsurance Net of Inuring Reinsurance

By Steve Malerich and Jack Liu

The Financial Reporter, September 2024

With coinsurance of an existing block of long-duration insurance contracts, there may be existing reinsurance that remains in force. The new coinsurance is typically net of such “inuring reinsurance.” In this situation, the new reinsurer does not reimburse for claims recovered from the existing reinsurer. In other words, the original reinsurance coverage inures to the benefit of the new reinsurer.

Since the new reinsurer is not responsible for claims recovered under the existing treaties, it is typical for the new coinsurance to provide allowances to the ceding entity for payment of the premiums under the existing reinsurance.

In this article, we look at approaches that the new reinsurer might apply to account for the effects of inuring reinsurance.

Objectives

As in several previous articles about accounting for ceded reinsurance, we evaluate different approaches in relation to three objectives—compliance, performance and simplicity.

Compliance relates to formal guidance, including authoritative standards of the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) and non-authoritative guidance published by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA).

Performance aligns accounting results with the substance of coverage and with rationale given by accounting authorities for their decisions.

Simplicity seeks one approach that can be applied to all long-duration treaties providing coverage net of inuring reinsurance.

Form and Substance

In its Basis for Conclusions of the pre-codification reinsurance standard, Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 113, the FASB stated that, “An assuming enterprise generally accounts for a reinsurance contract in the same manner as an insurance contract sold to an individual or non-insurance enterprise, …” (¶47). Neither codification nor the adoption of Accounting Standards Update No. 2018-12 did anything to change this expectation.

Policyholder allowances, however, are generally not present in insurance contracts and there are no explicit provisions in GAAP for an assuming entity to deal with recurring allowances. The reinsurer must therefore work without explicit guidance on accounting for them.

When a treaty describes coinsurance premiums as net of inuring reinsurance premiums, its form suggests a negative element in the coinsurance premium. One might therefore conclude that accounting should follow that form. That approach, however, will sometimes produce results that are inconsistent with FASB expectations.

Alternatively, the substance of this allowance might be seen as an exchange—replacing inuring recoveries in the coinsurance benefit stream.

Illustration

In this article, we illustrate accounting for an assumed block of universal life contracts with a secondary guarantee. The business has been in force long enough that remaining policyholder account values are declining, with the secondary guarantee growing in significance. A substantial portion of the mortality risk is covered under existing yearly renewable term (YRT) reinsurance. The coinsurance treaty provides allowances for actual YRT premiums, expressed as a reduction in the assuming entity’s share of policy charges.

For simplicity, we use the term “cash flows” from the perspective of the insurance element. Policy charges are cash flows, but deposits are not; excess payments are cash flows, but fund withdrawals are not.

For ease of illustration:

- The remaining life of the business is collapsed into seven years.

- The inability to collect mortality charges, due to the secondary guarantee, is expressed in the form of negative loads.

- YRT allowances equal YRT premiums.

- Investment return equals the crediting rate of 3.5% (no investment margin).

- The initial consideration and assumed liability equal the ceding entity’s net liability of 50,000.

- Benefit ratio measurements pivot on the initial assumed liability.

- All cash flows occur at the end of year.

- There are no variances from expected cash flows.

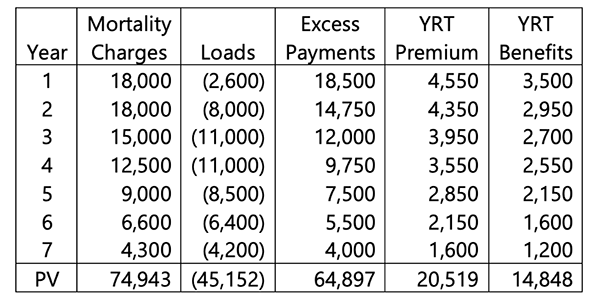

- There are no assumption changes. (see Table 1)

Table 1

Underlying Contract Cash Flows

As shown in Table 1, we expect Loads (the effects of the secondary guarantee on collectible charges) to increase in magnitude for the first few years then continue to increase in proportion to Mortality Charges.

With time, YRT premiums and benefits both increase in proportion to their direct counterparts, suggesting more efficient use of the secondary guarantee among the largest, most heavily reinsured policies.

YRT Allowances—Revenue Approach

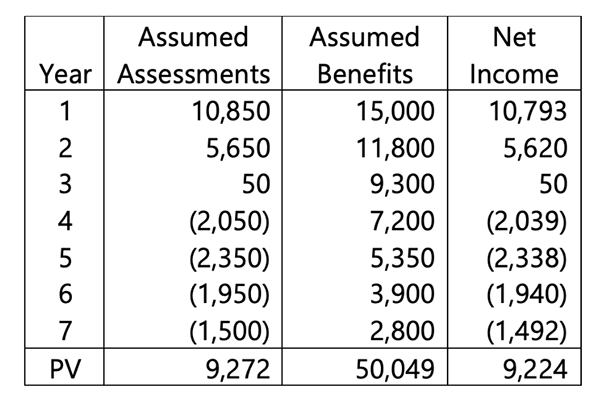

Following the form expressed in the coinsurance treaty, the assuming entity might view YRT allowances as negative revenue. As shown in Table 2, assumed assessments equal the sum of underlying mortality charges and loads, minus YRT premium allowances. Assumed benefits equal direct excess payments minus YRT benefits.

Table 2

Revenue Approach

Pivoting on the assumed liability, the benefit ratio is:

b = [PV0(Benefits) - Liability0]/PV0(Assessments)

= (50,049 - 50,000) ⁄ 9,272

= 0.5%

With a benefit ratio of 0.5%, we expect profits to be 99.5% of revenue in all years. But we expect revenue to turn negative about halfway through the remaining life of the business. A positive percentage margin on negative revenue means we expect to see losses in those later years. The additional liability for insurance benefits sustains an expectation of profits followed by losses—a condition that it is meant to alleviate.

According to ASC 944-60-25-9, “In those situations, the liability shall be increased by an amount necessary to offset losses that would be recognized in later years.” Consequently, the simplicity of the revenue approach is lost in the need for further adjustment of the liability.

YRT Allowances—Benefit Approach

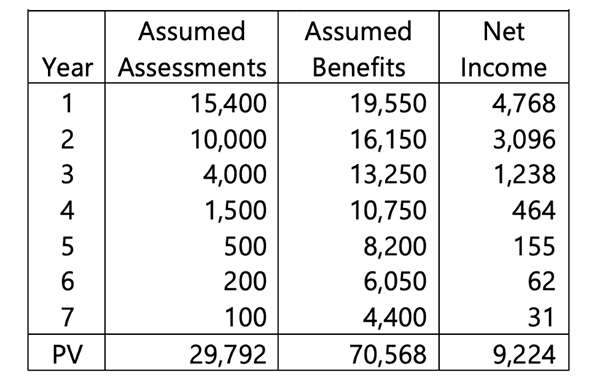

Rather than adjusting the results of the revenue approach, the assuming entity might look through the form of the allowances to their substance—replacing YRT benefits in the coinsurance benefit stream. As shown in Table 3, assumed assessments equal underlying assessments. Assumed benefits equal direct excess payments minus YRT benefits plus YRT premium allowances.

Table 3

Benefit Approach

Pivoting on the assumed liability, the benefit ratio is:

b = [PV0(Benefits) - Liability0]/PV0(Assessments)

= (70,568 - 50,000) ⁄ 29,792

= 69.0%

With a benefit ratio of 69.0%, we expect profits to be 31.0% of revenue in all years. With positive revenue expected in all years and a constant margin, there is no expectation of future losses and thus no need to further adjust the resulting liability.

Traditional Contracts

For traditional insurance contracts the combination of level premiums and increasing YRT premiums can lead to instances where ultimate YRT premium allowances are expected to exceed direct premiums of the underlying contracts. In those instances, coinsuring traditional business net of inuring reinsurance can again lead to an expectation of profits followed by losses for the assuming entity if the revenue approach is applied to liability calculations.

In the development of targeted improvements to the accounting for long-duration contracts, the FASB concluded that limiting net premiums to 100% of gross premiums made ASC subtopic 944-60 unnecessary for traditional contract liabilities. For this business, the revenue approach could create a situation that the FASB expected would not happen; applying that approach would likely be seen as inconsistent with FASB intent and therefore unacceptable.

Other Considerations

Looking beyond the simplicity of the above illustration, other considerations could help to avoid the problem of expected future losses under the revenue approach.

- When assuming universal life contracts, it might be reasonable to start with an initial assumed reserve of zero. In this way, the initial consideration would be considered a front-end load and amortized into assessments. This might be sufficient to maintain a stream of positive assessments for the life of the business. (Applied to the example, this would reduce the problem of negative assessments under the revenue approach but would not eliminate it.)

- When assuming traditional contracts, it might be reasonable to treat the initial consideration as a premium. Rather than fixing an initial reserve, this premium is added to the present value of recurring premiums to determine the net premium ratio. The initial reserve, after collection of the initial premium, would equal the product of this premium and the net premium ratio. Any profit margin in the initial premium would be deferred and its amortization might be sufficient to avoid losses related to negative revenue in later years.

- For either universal or traditional contracts, investment margin earned from assets backing the liabilities might be sufficient to offset losses from the reserve calculation.

Though each of these considerations might avoid the problem of expected future losses for some blocks of business, none of them can guarantee that result for all blocks of business. For both universal and traditional contracts, the objective of finding one approach that can be consistently applied still argues against the use of the revenue approach to account for YRT premium allowances.

Conclusions

In this article, we consider two approaches to accounting for inuring reinsurance in a coinsurance treaty. Both approaches treat inuring recoveries as a reduction to the assuming entity’s benefit obligations. They differ in whether they treat YRT premium allowances as a reduction to revenue or as an added benefit.

Given the lack of explicit guidance on accounting for allowances, either approach might satisfy the compliance criterion. In some instances, however, the revenue approach would produce results that are inconsistent with performance expectations and might even be judged incompatible with accounting standards codification. As such, the revenue approach fails the simplicity objective. Treating YRT premium allowances as benefits overcomes the performance concerns and can be applied consistently without regard to the specific relationship between the allowances and underlying revenue.

Statements of fact and opinions expressed herein are those of the individual authors and are not necessarily those of the Society of Actuaries, the newsletter editors, or the authors’ employer.

Steve Malerich, FSA, MAAA, is a director at PwC. He can be reached at steven.malerich@pwc.com.

Jack Liu, FSA, MAAA, is a senior manager at PwC. He can be reached at rongjia.liu@pwc.com.