Mind Matters: The Role of Re/insurers in Supporting the Mental Health (and Wellbeing) of our Policyholders

By Corinne Kenny

Reinsurance News, April 2022

It's hard to talk about mental health without talking about the COVID-19 pandemic. They've become inseparable and rightly so. COVID-19 has upended our fundamental wave of life and brought fear, grief, economic downturns, social isolation, and uncertainty. Mental health is quickly garnering more attention from public and private sectors alike.

But it's important to acknowledge that mental health was a rising concern before the pandemic. In 2019 (pre-pandemic), mental health conditions affected one in 10 people globally. They have been, and continue to be, a main cause of disability and early retirement in many countries—a major burden to economies—costing trillions every year.

- Two of the most common mental health conditions—depression and anxiety—cost the global economy USD 1 trillion each year.[1]

- By 2030, mental health conditions cumulatively are estimated to cost the world economy approximately USD 6 trillion.[10]

A position paper from insurance industry's Chief Risk Officer Forum in December 2021 called mental health "the hidden crisis.” I don’t think it's a "hidden crisis," it's certainly front and center—likely the most salient it will ever (hopefully) be in my lifetime.

What can we do about it? It's time for the insurance industry to seize the moment and play a larger role to build a more resilient society. Leveraging the use of technology, improving the products and services we provide and moving toward prevention through early intervention and ongoing support will be critical, something Swiss Re is committed to tackling on a global level.

Burnout is on the Rise …

Even before the pandemic, burnout and work-related stress were at concerning levels. A Deloitte study on workplace health in the US suggests more than 70 percent of respondents have experienced burnout in their current job, with over half citing more than one occurrence.[2]

US employees are not alone—the mental health crisis is so widespread in developed countries that the World Health Organization (WHO) has updated burnout in the 11th Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) with a more detailed definition, although it is not (yet) classified as a medical condition.[3]

- According to the WHO, burnout is an occupational syndrome resulting from “chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed” with three characteristics: (1) Feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion; (2) increased mental distance from one’s job, or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one’s job; and (3) reduced professional efficacy.

The pandemic has only amplified the mental health crisis. People are more stressed about their job security, are working longer hours and taking on more responsibilities, while caring for family members—all of which can lead to burnout, lower productivity, and higher turnover.[4][5]

Burnout may also lead to symptoms of depression, requiring treatment, and sometimes results in the partial or total inability to work. Although burnout and work-related stress is related to clinical mood disorders such as anxiety or depression, it's distinctly associated with work and work hours. The prevalence of burnout varies with occupation, social support, and country. Survey findings suggest that burnout rates are higher in women than men and higher in younger age groups than older employees.[6]

- Burnout doesn’t go away on its own and, if left untreated, can lead to serious psychological and physical illnesses like severe depression and other somatic diseases.

- Burnout is most associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD) and cardiovascular risk factors, including high blood pressure.[6]

- The most effective workplace intervention is to redesign work to reduce exposure to stressors, while failing is to change jobs or be reassigned to other work.

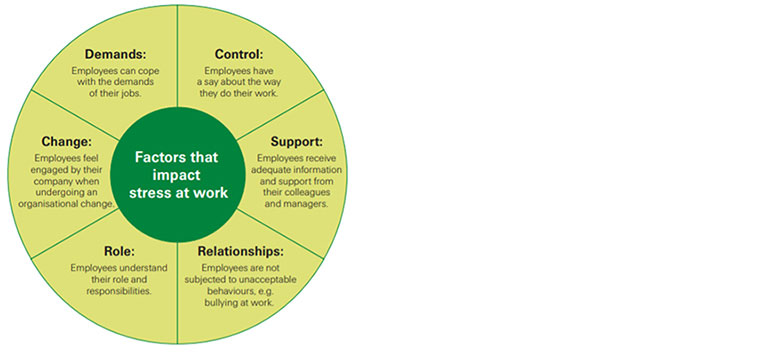

When managed properly these workplace stressors can be reduced, and in turn, reduce the amount of workplace stress[7] (see Figure 1):

Figure 1

Factors That Impact Stress at Work

… And Health Care Workers Might be the Most Vulnerable

Burnout rates are higher among health care providers and first responders, who now face added stress and responsibility because of the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the Association of American Medical Colleges, "multiple survey data now shows health care workers responsible for providing direct care for COVID-19 patients are more likely to have depression, anxiety, and mental distress. These mental health issues may be related to psychological distress from witnessing COVID-19-related deaths, extra-long work hours, and work-life imbalance." What's worse, The Washington Post/Kaiser Family Foundation survey found that 29 percent of health care workers in hospitals have considered leaving the medical field.[8]

- Too many health care workers are suffering from burnout, yet they are less likely to receive adequate care due to linger stigma and even fear of getting their medical license withdrawn.[9]

- This problematic frontline burnout may reduce productivity, increase turnover, and possibly decrease patient's access to care as the medical provider gap grows.

If mental health is the next pandemic, burnout (particularly among frontline workers) might be one of the primary drivers.

Blurred Boundaries? The Spectrum of Mental Health and Mental Wellbeing

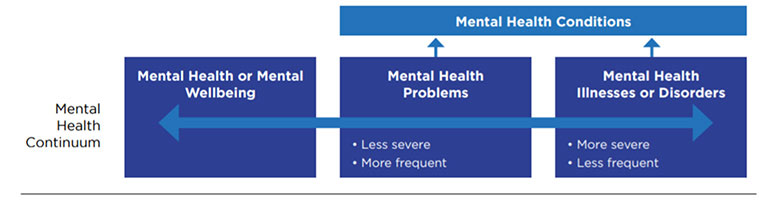

Mental wellbeing refers to a state of mental health in which an individual can adequately cope with the normal stresses of life, demonstrates resilience in the face of adversity, and participates in his or her community through productive pursuits such as work or volunteering. The full spectrum of mental wellbeing can include both positive affects like resilience, happiness and life satisfaction, and negative effects such as anxiety or irritability. (See Figure 2)

Figure 2

The Mental Health Continuum

In short, mental wellbeing is more than the absence of a mental health condition. Although mental wellbeing might seem less “tangible” than a diagnosed mental health condition, the cumulative effects are real.

That's why Swiss Re has named mental wellbeing as one of six lifestyle factors and areas for research, dubbed our Big Six Lifestyle Factors. These factors can supplement traditional risk assessment methods to help insurers evaluate risk more accurately and adopt a multifaceted view of health that considers the interaction of physical, mental and lifestyle elements. To understand our insurance customers more holistically, it's vital to consider the continuum of mental health (and the remaining lifestyle factors).[10] Let's start by unpacking the physical impacts of mental health and mental wellness.

- Mental wellbeing is not limited to the brain. In fact, your mental wellbeing affects your heart and body too. Health care professionals call this the “mind-heart-body” connection.

- In a recent meta-analysis of 128 studies, the American Heart Association showed clear associations between mental wellbeing and key cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors such as body mass index (BMI), blood pressure, blood lipids, and glucose metabolism.[11]

- People who experienced chronic and traumatic stress, anger and hostility, and pessimism were more likely to have high blood pressure, high cholesterol levels, and weight-related issues resulting in higher risk for CVD or type 2 diabetes.

On the flip side, positive mental wellbeing was shown to enhance clinical cardiovascular measurements. Mindfulness, for example, has been associated with normal fasting glucose level (<100 mg/dL) and a lower BMI.[12][13]

A key to improving mental health may in fact lie with improving our physical health, and vice versa. Even a 10-minute brisk walk increases mental alertness, energy and positive mood, and exercising regularly can increase our self-esteem and reduce stress and anxiety.

Is Mental Wellbeing Associated With Lower Disease and Mortality Risk?

It's complicated. Mental wellbeing is hard to quantify and measure and each study seems to use slightly different definitions. Some focus on specific sub-clinical measurements, like happiness or social connectedness, while others concentrate on clinical components of mental health, like anxiety disorders or depression, which is easier to measure and quantify. Long-term robust research is often lacking too, making it hard to draw bold causal conclusions. Further, due to subjectivity and complexity of mental wellbeing, there are few holistic models of mental wellbeing that have wide-spread use in the general population and have enough robust evidence to use in risk assessment.

But we can draw some broad generalizations by looking at the right studies. Recent meta-analyses suggest that subjective wellbeing measures such as sense of purpose, optimism, and positive affect can be protective against premature overall mortality and may be significantly associated with a decreased risk of cardiovascular events (see Fig.3).[14][15][16]

It's worth noting that mental wellbeing may also have effects on outcomes other than mortality, which are not as objective and easy to measure. Additional studies indicate greater wellbeing levels are related to lower risk of cardiometabolic diseases, infectious illness, and physical decline. The impact on cancer mortality is less clear. Moving beyond health outcomes, mental wellbeing has also been related to higher levels of employment, income, and work retention.[17] On the other hand, negative psychological factors like anxiousness, work-related stress or pessimism can also impact health outcomes—but typically in the opposite direction.

Building a More Resilient Future, Together

More people are recognizing the vital role mental health plays in overall health and wellness. This trend was growing before COVID-19 and the pandemic has only accelerated our collective awareness. We have a unique opportunity to use this heightened understanding to move beyond awareness and into action.

Re/insurers have an important role to play providing expertise and using different “tools in their toolkit” to: 1) Better understand and prevent mental illness, which contributes to a more resilient society; and 2) improve insurance products and the customer experience associated with mental health.

Here are a few ideas how our industry can focus on championing an action-oriented approach to building a more resilient future:

- Improved application questions (that factor in co-morbidity risk factors) can ensure more accurate risk assessment. Understanding the link between body and mind with improved application questions that take into consideration co-morbidity risk factors can lead to more accurate risk assessment.

- Digital apps and tech-based solutions can play a role in promoting positive affect, building mental resilience, and managing stress and anxiety, but are only part of the equation.

- Including early and tailored intervention mechanisms into the product design can prevent poor mental wellbeing from becoming chronic. Here the biopsychosocial approach works well.

- Consider flexible benefits or additional coverage options to support policyholders experiencing poor mental wellbeing.

- Don't forget about the wellbeing of your own workforce! Promoting positive mental wellbeing amongst your team can help prevent burnout and turnover.

Statements of fact and opinions expressed herein are those of the individual authors and are not necessarily those of the Society of Actuaries, the newsletter editors, or the respective authors’ employers.

Corinne Kenny, Global UW R&D manager, Swiss Re. Corinne can be contacted at corinne_kenny@swissre.com.