It Didn't Cost a Pennie

By Greg Fann

In the Public Interest, January 2021

“With a two-step regulatory change, Pennsylvania has transformed its ACA marketplace. The measure is probably the most impactful single step a state has taken to improve its marketplace. And the move won't cost the state a cent.”—Andrew Sprung, xpostfactoid: Pennsylvania transforms its ACA marketplace with one sentence

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) provides states with multiple opportunities to improve their local markets. Most options involve a significant investment, both staff time and financial resources. Last year I noted a cost anomaly; “Enforcing ACA rules appropriately aligns metal level pricing, reduces net premiums, attracts a healthier enrollment mix, and ultimately reduces gross premiums in the marketplace. This dramatically improves markets at virtually no cost.”

Pennsylvania’s 2021 Response

Pennsylvania was one of two states that migrated to a state-based exchange in 2021. The shiny new “Pennie” has received considerable attention. Meanwhile, the larger impact on the Pennsylvania marketplace, “the most impactful single step a state has taken to improve its marketplace,” has gone mostly unnoticed. Pennsylvania adopted new regulations in May 2020 which require prescriptive “induced demand” factors. In editorial fairness, it’s not hard to understand that Pennsylvania news is littered with articles directing consumers to the new enrollment process rather than informing them that “the induced demand factors on the plans they purchase will be calculated by squaring the actuarial value, subtracting the actuarial value, and adding 1.24.”

While the new enrollment process attracts the headlines, in fact it is the prescriptive factor change that provides individual market enrollees with tangible financial benefits. The Pennsylvania “Rate Filing Guidance” accelerates the shift to market equilibrium, where lower income consumers benefit from adherence with community rating rules. Specifically, compliance enforcement is strengthened by limiting subjective development of induced demand factors, which unencumbered stray toward lower silver premiums (which determine premium subsidy levels) through Metalball and away from the ACA’s nondiscriminatory tenets.

The National Landscape

Pennie had one analysis drawback. As Pennsylvania moved off the federal exchange, its 2021 landscape results were not included in the annual government report illustrating premium detail in federal exchange states. Even without the strong Pennsylvania movement in the annual data, I believe the national results suggest that 2021 will be the ACA’s most successful year.

A significant indicator of market success is state response to 2017 regulatory action, which enhanced federal funding and converted claim payment reimbursements to insurance companies into premium vouchers for lower income enrollees. The “enhanced federal funding” segment is the real construction phase of the ACA’s makeover and requires focused state rate review activity in alignment with the new Pennsylvania prescriptive guidance, not merely state acknowledgment of appropriate metal level premium alignment. States partially responded in the first year of 2018, markets stagnated in 2019 and 2020, and there is noticeable improvement in 2021.

A quick, simplistic way to understand premium alignment, distance to equilibrium, and market attractiveness is to compare the lowest gold plan to the benchmark plan (a colleague has developed a more refined methodology). If a gold plan is cheaper than the benchmark plan, enrollees can purchase a high value plan for less than an “affordable” rate; the ACA defines affordability as a fixed percentage of income and allows enrollees with incomes below 400 percent of the Federal Poverty Level to purchase the benchmark plan for an affordable premium. For purposes of this article, the average lowest cost premiums for each state as calculated by KFF are compared.

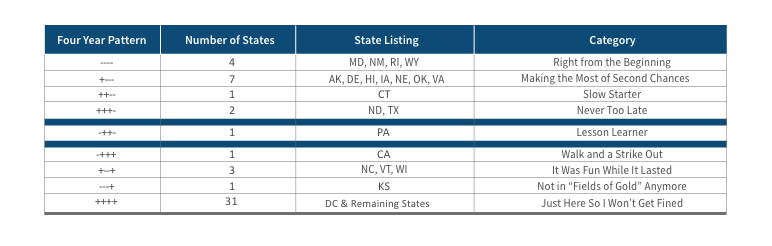

The first column in Figure 1 displays the relationship of the lowest gold premium to the benchmark premium. The “-” simply means that the lowest gold plan is cheaper than the benchmark plan; “+” means it is higher. Relationships for 2018–2021 are displayed as one field. For example, “++--” means that the lowest gold premium in CT was higher than the benchmark plan in 2018 and 2019, but lower in 2020 and 2021.

Four “right from the beginning” states have succeeded in having lower gold premiums all four years, albeit for different reasons. Wyoming was a monopoly state until 2021, and its single issuer could price its products without fear of Metalball competition. The Rhode Island state exchange has been active keeping Lionfish out of its market. While the specific beneficial logistics in Maryland and New Mexico are less direct, active engagement by consumer advocates and state exchange professionals who understand ACA dynamics have made their markets work.

Seven states waited a year (“making the most of second chances”) to have a gold plan cost less than the benchmark plan and one state (“slow starter”) took two years. North Dakota and Texas were “never too late” and achieved having a gold plan lower than the benchmark in 2021, which is favorable to consumers as the benchmark plan premium determines the subsidy level; Texas is notably one of the three states with over one million enrollees.

Pennsylvania is uniquely the “lesson learner,” having a strong market in 2018, getting crushed in 2019 as benchmark premiums fell 27 percent while bronze/gold only fell 8 percent/4 percent, and implementing Focused Rate Review in 2021 and significantly improving local markets.

California (“walk and a strike out”) started strong in 2018, primarily due to the Sharp and Kaiser movement toward equilibrium, but those plans regressed to the Metalball market and drifted away from equilibrium in 2019 and 2020, and remained unfavorable in 2021. Three states (“it was fun while it lasted”) had favorable conditions in 2019 and 2020 but are sandwiched by more challenging years in 2018 and 2021. A drought hit Kansas (“not in fields of gold anymore”) after a three year harvest as gold premiums moved above benchmark rates. Finally, most states have not put forth helpful efforts to strengthen their marketplaces. They do what they are required to do to avoid trouble (as a Seattle Seahawks running back complied with post-game availability to the media but was not a useful interviewee, answering every question “I’m just here so I won’t get fined”) with federal authorities, but they have not actively improved market dynamics. Some had planned to take action in 2021, but understandably had their priorities and resources shifted by COVID-19.

Conclusion

The obvious question should be obvious. If it really doesn’t cost anything, it reduces premiums for low-income enrollees, and it benefits insurers, why haven’t more states implemented Focused Rate Review? Why has construction on the ACA makeover stalled after initial progress in 2018? It is a question I have been asking over the last two years and I have received a few consistent answers.

As health care is the second largest state budget item, even a small portion of the “cost” is often a defensible explanation. That doesn’t apply here; a state needs to hire actuaries that understand ACA dynamics to implement Focused Rate Review, but that’s immaterial relative to the billions of dollars in underfunded premium subsidies. A valid reason is lack of understanding of elusive ACA markets; this is partially due to recent public discussion favoring the litigation surrounding the ACA and potential replacement legislation over a quantitative dissection of developing market dynamics. Some states have simply said they believed the ACA was temporal and significant self-directed changes would be disruptive and not a prudent time investment for a short-term market environment. Other states have viewed the market changes through a political lens and have sought to maintain fidelity to original ACA product relationships without regard to market benefits.

What is the rationale to not implement Focused Rate Review in 2022? Let us address each barrier. Knowledge and understanding? That has improved each year, and hopefully you can share this article with your state officials. Temporal environment? Let’s hope not. ACA markets are stronger than ever, they will continue to strengthen, and we need to avoid the federal temptation to meddle with improving markets. Politics? With the presidential office being occupied by the man who was vice-president when the ACA became law, there should be more focus on market efficacy and less inclination to be concerned with political dynamics. Costs? There are no real costs involved with Focused Rate Review. It can be done. It should be done. It has been done. Look at Pennsylvania. They did it. Their market is stronger in 2021. And it didn’t cost a Pennie.

Statements of fact and opinions expressed herein are those of the individual authors and are not necessarily those of the Society of Actuaries or the respective authors’ employers.

Greg Fann, FSA, MAAA, is the chair of the Social Insurance & Public Finance Section Council and a consultant with Axene Health Partners, LLC. He can be reached at greg.fann@axenehp.com.